The Revd Jeania Ree V. Moore considers the challenges of the covid-19 pandemic, her journey towards veganism and the spiritual benefits of Lenten fasts.

When COVID-19 hit home in March 2020, shortages of tofu, tempeh, and toilet paper were some of the most immediate indicators of the oncoming pandemonium in local stores where I lived. Plant-based eating is popular in Washington, D.C., and as with all household necessities, people were stocking up. Faced with the absence of some of my preferred vegan items, I began purchasing eggs and dairy, moving these items which had previously been taken off of my grocery list back into the “basic necessities” column. Rather than embrace the less-processed plant protein sources that were available, I fed my fear of “not having enough” and reverted to the false sense of security in animal products which I had previously disavowed.

COVID-19’s impact on dietary preferences may seem to be the least of our concerns when many people do not have enough to eat. Yet, it is precisely the linkages between fear and scarcity, faith and abundance which veganism identifies that COVID-19 has spotlighted and magnified. The global pandemic has challenged our frameworks for “enough” with fear of the unknown, resulting in projections of scarcity that alter or amplify already problematic behavior. Here in the U.S., the fear of meat shortages was taken to an extreme when a presidential order prioritized meatpacking operations over the safety and health of workers of color during a pandemic. This grotesque, disorganized calculus reflects the dynamics implicit in the meat industry, and in a capitalist society more broadly, which secure the good of one (buyers) at the expense of another (factory workers and farmed animals). In a global pandemic, this unequal exchange becomes an unspoken rule guiding daily interactions: every woman—every creature—for themself. And behind this rule sits a more insidious maxim: that ethics is a luxury.

COVID-19’s impact on dietary preferences may seem to be the least of our concerns when many people do not have enough to eat. Yet, it is precisely the linkages between fear and scarcity, faith and abundance which veganism identifies that COVID-19 has spotlighted and magnified. The global pandemic has challenged our frameworks for “enough” with fear of the unknown, resulting in projections of scarcity that alter or amplify already problematic behavior. Here in the U.S., the fear of meat shortages was taken to an extreme when a presidential order prioritized meatpacking operations over the safety and health of workers of color during a pandemic. This grotesque, disorganized calculus reflects the dynamics implicit in the meat industry, and in a capitalist society more broadly, which secure the good of one (buyers) at the expense of another (factory workers and farmed animals). In a global pandemic, this unequal exchange becomes an unspoken rule guiding daily interactions: every woman—every creature—for themself. And behind this rule sits a more insidious maxim: that ethics is a luxury.

When I started my journey toward veganism, becoming vegetarian in 2018 and vegan during Lent in 2019, I acknowledged these notions as untruths. I rejected an isolated ethic and the idea that ethics is ultimately a luxury, affirming that solidarity with farmed animals via healthy plant-based eating should not be a privilege. The fact that it so often is indicts—and invites us to change—society, not ethics. Over two-thirds of agricultural land feeds farmed animals, not people; if we re-routed this, we could lower global hunger. Our inability to properly realize abundance contributes to the simultaneous realities of massive hunger and massive food waste. We should work to make a different world possible.

Right before the pandemic set in, I wrote the following reflection on what spiritual fasting and abstaining from animal food products taught me about Lenten liberation. Since then, I have at times retreated from this way of living. Re-reading my words now is less reproach than reminder. Veganism reminds us that there is no final “achievement” or “failure,” but continual decision, again and again, to eat with a different world in mind. The Sarx Lent Guide is a timely resource for our pursuit of this different world, seeking faith in abundance, not fear of scarcity, for all.

SOJOURNERS MARCH 2020 column: “Why Fasting is Actually About Liberation”

FOR MUCH OF my life I thought of Lent primarily as a season of personal piety, a self-contained period of reflection on individual sin and repentance. This penitential practice was limited in both scope and duration: It had little to do with others apart from me and God, and its impact did not extend beyond Easter. I approached a central component of Lent—the fast—like a trial, a test of willpower that pitted God against some “thing” I had given up, often a food (usually cheese or dessert). Much to my chagrin, in this personal test of will, God did not always win out. Overall, I was grateful and relieved each year when Lent ended.

Two years ago, things changed. As a dairy and meat aficionado who unexpectedly found herself a convert to vegetarianism and pondering veganism, I suddenly had a new relationship with chosen fasts. (The cause: Eating Animals, a book on factory farms written by Jonathan Safran Foer, collaborating with Jewish ethicist Aaron Gross. Read at your own dietary risk.) Vegetarianism helped me engage fasting as something internally motivated by ethical and spiritual concerns, rather than externally imposed. Participating in my church’s annual Daniel Fast later that year deepened this new experiential understanding. Based on Daniel 1 and featuring weekly 12-hour periods with no food, this fast helped me experience how fasting is not about willpower, but surrender. It taught me about hubris, humility, and moment-by-moment reliance upon God, which often involved other people.

These experiences reintroduced me to fasting as a meaningful mode of connection to God and the world. Rather than being solely between me and God, vegetarianism and the Daniel Fast engaged my relationships with others, whether through bouts of “hangry”-ness, gratefully received gifts of food, a newfound awareness of those whose encounters with hunger far surpass mine, or my ongoing attempts to relate differently to farmed animals. Instead of having a specified end date, fasting’s impact endured, changing my relationships with God and the world around me. Fasting became, in effect, a channel for justice. Through fasting, I learned to nourish a different kind of hunger.

These experiences reintroduced me to fasting as a meaningful mode of connection to God and the world. Rather than being solely between me and God, vegetarianism and the Daniel Fast engaged my relationships with others, whether through bouts of “hangry”-ness, gratefully received gifts of food, a newfound awareness of those whose encounters with hunger far surpass mine, or my ongoing attempts to relate differently to farmed animals. Instead of having a specified end date, fasting’s impact endured, changing my relationships with God and the world around me. Fasting became, in effect, a channel for justice. Through fasting, I learned to nourish a different kind of hunger.

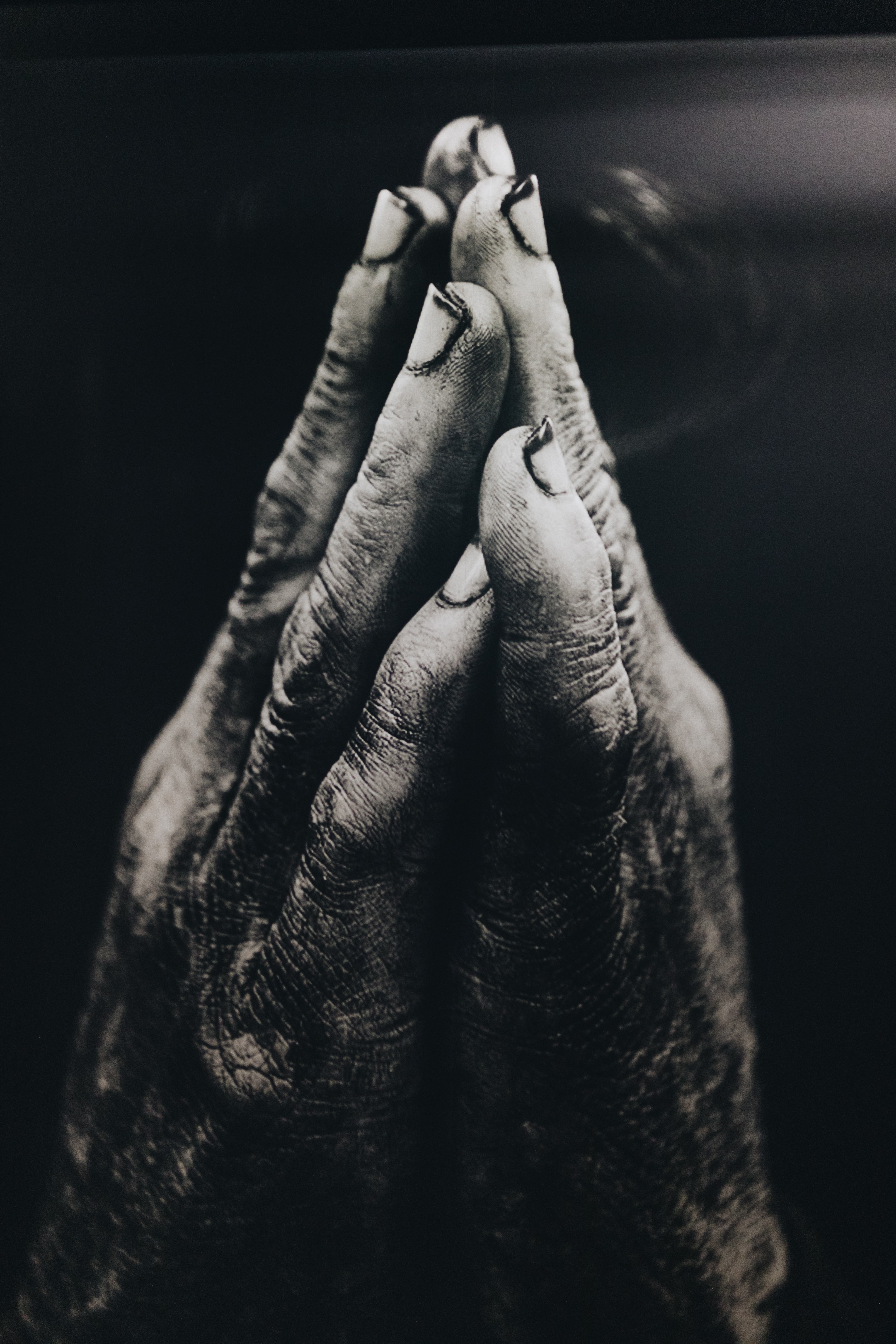

In the Bible, fasts are tools of spiritual preparation that help individuals or groups address social or political crises or endeavors—for example, Esther’s plea before King Ahasuerus, Daniel’s captivity in the Babylonian court, and Jesus’ 40 days in the wilderness to start his ministry. The prophet Isaiah writes: “Is this not the fast that I have chosen: to loose the bonds of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, to let the oppressed go free, and that you break every yoke?” Isaiah reminds us that fasting is not about piety, but liberation. As a spiritual practice righting relationship with God, fasting involves our relationships with others.

At a time when social and political crises of all sorts loom, Lenten fasts are vital tools for individual and communal spiritual health. Lent is an opportunity to acknowledge and address that sin—and salvation—is corporate. Borrowing from Mordecai, Lent is for such a time as this.

Reprinted with permission from Sojourners, (800) 714-7474, www.sojo.net.

The Revd Jeania Ree V. Moore is a writer, United Methodist deacon, and doctoral student in religious studies and African American studies at Yale University.

The Revd Jeania Ree V. Moore is a writer, United Methodist deacon, and doctoral student in religious studies and African American studies at Yale University.