Revd Dr Trystan Owain Hughes explores the interrelatedness of all living beings and demonstrates how the common origin and essential unity of creation necessitates that every animal is treated with respect, compassion and love.

In the Dreamworks film How to Train your Dragon (2010), the lead character, Hiccup, has from an early age been taught that his own people, the Vikings, kill dragons. Their instinct to destroy these magnificent flying creatures is, explains his teacher, simply part of their nature and as such it cannot be changed. Later in the film, Hiccup finds an injured dragon and discovers deep feelings of care and compassion towards him, and so he rebels against the long-standing Viking tradition by refusing to kill the helpless beast. ‘I wouldn’t kill him because he looked as frightened as I was;’ he explains to his girlfriend Astrid, ‘I looked at him and I saw myself.’

In the Dreamworks film How to Train your Dragon (2010), the lead character, Hiccup, has from an early age been taught that his own people, the Vikings, kill dragons. Their instinct to destroy these magnificent flying creatures is, explains his teacher, simply part of their nature and as such it cannot be changed. Later in the film, Hiccup finds an injured dragon and discovers deep feelings of care and compassion towards him, and so he rebels against the long-standing Viking tradition by refusing to kill the helpless beast. ‘I wouldn’t kill him because he looked as frightened as I was;’ he explains to his girlfriend Astrid, ‘I looked at him and I saw myself.’

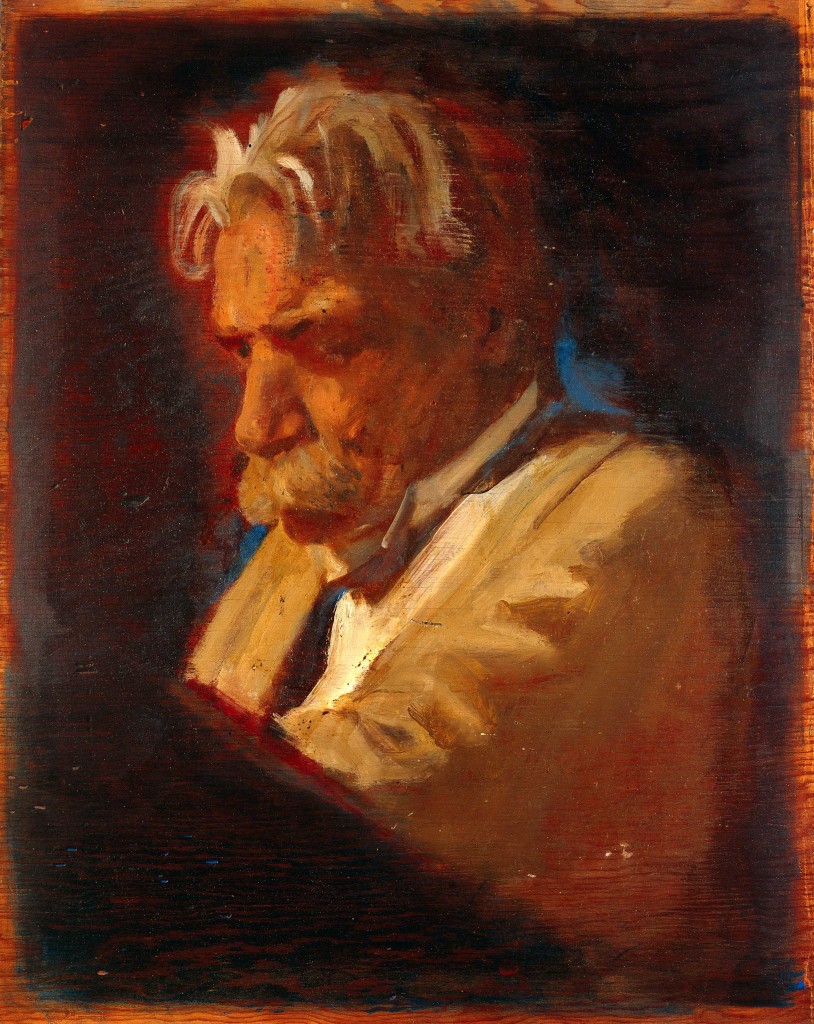

We live in a world in which we rarely recognize that non-human forms of life are worthy of the compassion and respect we bestow on fellow humans. The philosopher and medical missionary Albert Schweitzer urged us to have a ‘reverence for life’. The phrase suggests an attitude of awe and ultimate respect, and carries with it an overwhelming sense of moral responsibility towards life and all of creation. At the heart of the concept is interconnectedness. All of life is related, and thus we should be able to empathize with all suffering, whether human or not. ‘The tiny beetle that lies dead in your path – it was a living creature,’ wrote Schweitzer, ‘struggling for existence like yourself, rejoicing in the sun like you, knowing fear and pain like you.’ Most of us already regard human life as inherently important, but rarely do we value the lives of non-human creatures. Every creature will itself hold to the importance of its own life, albeit unconsciously, and this realization should lead us to solidarity with all forms of life – forms of life that are just like us. In this sense, our relationship with nature is far more intimate than we might think: ‘Wherever you see life,’ wrote Schweitzer, ‘that is yourself!’

Albert Schweitzer

The concept of reverence for life helps us to recognize the infinite value of all created living things. Yet the materialistic world in which we live patently regards ‘life’ very differently. Too often the pursuit of economic growth, efficiency and productivity is regarded as more valuable than the natural world. Animals on farms are not seen as inherently valuable in itself, but rather as ‘meat’ to be sold and consumed. E.F. Schumacher urged us to value instead ‘the inwardness of things’, the mysterious quality of every living being. ‘Anything that we can destroy but are unable to make,’ writes Schumacher, ‘is, in a sense, sacred, and all our “explanations” of it do not explain anything.’ The Bible supports such a conclusion and unequivocally advocates loving ethical guidelines for all of creation. In the Old Testament laws, for example, hunting as a sport is prohibited, the slaughter of animals for food is permitted only within strict guidelines that ensure the least suffering, and the Sabbath includes rest for domestic animals as well as humans. Furthermore, the wisdom tradition describes divine Wisdom as being embedded in creation (Job 12.7–10). It seems clear from Scripture that God loves animals for their own sake – a fact that biblical scholars inform us was quite possibly unique in the ancient Near East.

The present status quo, however, means that, to most of us, animals are regarded as having no real value in themselves, save their worth to us humans. Richard Holloway suggests that many animals in modern industrial farming experience a ‘double-dying’, as their everyday existence is as pitiful as the death they are destined to undergo. They live out their wretched lifespans in ‘crowded disease-prone torture’, at the end of which they may be transported hundreds of miles in overcrowded trucks to their slaughter. Our society continues to turn a blind eye towards heartless factory farming practices. Often they are not only tolerated but justified with the argument that animals are little more than unfeeling machines who don’t really ‘suffer’ in the human sense of the word. ‘Who hears when animals cry?’ asked The Smiths on their 1987 single ‘Meat is Murder’, and in the song they compare the whines of heifers to human cries of pain and suffering. Yet, in reality, to most of us today these whines are, in the words of Descartes, ‘no more than the creaking of a wheel’.

Once we recognize the essential unity of all living beings, we will see that life can never be considered a commodity – it cannot be possessed, competed for, or purchased. Even our pets are not owned by us, despite the fact that we may have paid for them. All living things exist in their own right, and from the moment we are born we are intricately bound up and belong to one another in the mystery of being. Thus, all parts of creation, whether or not they are physiologically close to us, are equally worthy of our attention, respect and love. All life wills to live, just as we ourselves do. We must appreciate that this will and drive are gifted by the creator and should, therefore, be taken seriously. Embracing this view will have huge implications on moral and ethical matters – not least on our attitudes towards the environment, food production, health care, emerging technologies, animal care, energy development, and so on. ‘Do not do any injury, if you can possibly avoid it,’ the great Welsh Celtic saint Teilo is purported to have said while reflecting on the natural world. When we begin to acknowledge creation as a unified whole, then we will recognise that the individual parts deserve our attention and compassion, not because they are useful or beneficial to us, but simply for their own sake. The whole web of life is valued and loved by God, not merely a single strand of it. It must, therefore, also be valued and loved by us.

Once we recognize the essential unity of all living beings, we will see that life can never be considered a commodity – it cannot be possessed, competed for, or purchased. Even our pets are not owned by us, despite the fact that we may have paid for them. All living things exist in their own right, and from the moment we are born we are intricately bound up and belong to one another in the mystery of being. Thus, all parts of creation, whether or not they are physiologically close to us, are equally worthy of our attention, respect and love. All life wills to live, just as we ourselves do. We must appreciate that this will and drive are gifted by the creator and should, therefore, be taken seriously. Embracing this view will have huge implications on moral and ethical matters – not least on our attitudes towards the environment, food production, health care, emerging technologies, animal care, energy development, and so on. ‘Do not do any injury, if you can possibly avoid it,’ the great Welsh Celtic saint Teilo is purported to have said while reflecting on the natural world. When we begin to acknowledge creation as a unified whole, then we will recognise that the individual parts deserve our attention and compassion, not because they are useful or beneficial to us, but simply for their own sake. The whole web of life is valued and loved by God, not merely a single strand of it. It must, therefore, also be valued and loved by us.

The Revd Dr Trystan Owain Hughes is Director of Vocations at the Diocese of Llandaff and vicar of Christ Church, Roath Park, Cardiff. He attained an MTh from Oxford University, with a thesis on suffering and contemplative prayer, and a PhD in church history from the University of Wales, Bangor. He is an acclaimed author whose publications include Finding Hope and Meaning in Suffering (SPCK, 2010), The Compassion Quest (SPCK, 2013), and Real God in the Real World (BRF, 2013). He is on the theological commission that assists the bench of Welsh Bishops. He blogs at www.trystanowainhughes.com/blog

Read more about Trystan’s thoughts on animals in his book The Compassion Quest (SPCK, London 2013), available at all good booksellers.