Michael Gilmour, Professor of New Testament and English Literature at Providence, University College explores the works of C.S Lewis; revealing a man with a deep love of animals and whose faith inspired him to emphasise their goodness and dignity in his world-famous novels.

Michael visiting the grave of Kenneth Grahame in Oxford

In the July 15, 1953 issue of Punch magazine, C. S. Lewis published the short poem “Impenitence.” Despite the religious-sounding title, this delightful text (seven non-rhyming stanzas of four lines each) is actually an apology for children’s literature. The “Impenitence” in question is Lewis’s defiance of critics—“wiseacres,” “kill-joys”— who demand the poet grow up, that he quit reading silly stories about dressed-up talking animals. Their words go unheeded: “[they] Shan’t detach my heart for a single moment / From the man-like beasts of the earthy stories.”

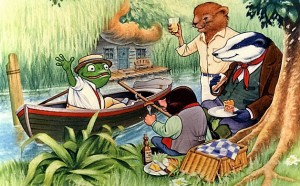

Lewis then names various talking animals enjoyed since childhood. Badger and Toad Hall take readers back to Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908). He mentions the titular characters in Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin (1903) and The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle (1905). There are nods to Homer, the fifteenth-century poet Robert Henryson (“shrill mouse”), and Lewis Carroll’s 1876 poem The Hunting of the Snark (“the Beaver doing / Sums with the Butcher!”).

Why are his critics so wary of these books? Lewis’s (very grownup) philosophical and theological musings on human and animal suffering (The Problem of Pain, 1940) hint at one possibility. He prefaces a rather unlikely illustration with a parenthetical caveat: “A modern example may be found (if we are not too proud to seek it there) in The Wind in the Willows where Rat and Mole approach Pan on the island.” There is wisdom in unlikely places but hubris—in this case synonymous with growing up—blinds some to it. Those with eyes to see, let them see, even if what they look at is Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Benjamin Bunny with all its crazy pictures. Children’s stories, after all, are potential vehicles for lofty ideas. What is Narnia, after all?

Why are his critics so wary of these books? Lewis’s (very grownup) philosophical and theological musings on human and animal suffering (The Problem of Pain, 1940) hint at one possibility. He prefaces a rather unlikely illustration with a parenthetical caveat: “A modern example may be found (if we are not too proud to seek it there) in The Wind in the Willows where Rat and Mole approach Pan on the island.” There is wisdom in unlikely places but hubris—in this case synonymous with growing up—blinds some to it. Those with eyes to see, let them see, even if what they look at is Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Benjamin Bunny with all its crazy pictures. Children’s stories, after all, are potential vehicles for lofty ideas. What is Narnia, after all?

“Impenitence” hints at a more specific reason why the poet defies his critics. In the fourth, which is to say middle stanza—a conspicuous location suggesting emphasis—Lewis moves from a summary of his detractors’ charges to an actual explanation why the menagerie of children’s stories matter.

Look again. Look well at the beasts, the true ones.

Can’t you see? … cool primness of cats, or coney’s

Half indignant stare of amazement, mouse’s

Twinkling adroitness.

The poet wants readers to recognize the continuity between imagined animals and real ones. Within the logic of these lines, to love a literary animal is to love a real animal. Alternatively, to lose affection for the one risks indifference toward the other. Lewis loved animals and the very idea of their human-caused sufferings horrified him. He insisted that a Christian worldview ought to acknowledge the goodness of all God’s creatures. It follows that any book generating sympathy for them, even those by Kenneth Grahame, Beatrix Potter, E. Nesbit, and the like, are most welcome. Lewis brings this line of argument to a head in the penultimate stanza and the enjambment connecting it to the last:

The poet wants readers to recognize the continuity between imagined animals and real ones. Within the logic of these lines, to love a literary animal is to love a real animal. Alternatively, to lose affection for the one risks indifference toward the other. Lewis loved animals and the very idea of their human-caused sufferings horrified him. He insisted that a Christian worldview ought to acknowledge the goodness of all God’s creatures. It follows that any book generating sympathy for them, even those by Kenneth Grahame, Beatrix Potter, E. Nesbit, and the like, are most welcome. Lewis brings this line of argument to a head in the penultimate stanza and the enjambment connecting it to the last:

…. And if the love so

Raised—it will, no doubt—splashes over on the

Actual archtypes,

Who’s the worse for that?

The love of literary animals “splashes” on to real ones. What a charming thought.

Lewis released “Impenitence” (1953) when halfway through publishing the Chronicles of Narnia (1950–1956). There is clear thematic overlap. In those novels also there is emphasis on the dignity and goodness of animals (whether or not they speak) and cruelty toward them is inevitably a mark of villainy, from Uncle Andrew’s experiments on a guinea pig in The Magician’s Nephew to the Calormenes’ practice of enslaving talking horses in The Last Battle. Unfortunately, adults tend to stop reading books like these. They lose the childlike wonder at the natural world such stories nurture. Like Lewis’s imagined cynics and critics, they no longer see any value in reading about pert Nutkin or Rat the oarsman. And once so disenchanted, Lewis fears, indifference toward the sufferings of actual animals is possible.

Lewis released “Impenitence” (1953) when halfway through publishing the Chronicles of Narnia (1950–1956). There is clear thematic overlap. In those novels also there is emphasis on the dignity and goodness of animals (whether or not they speak) and cruelty toward them is inevitably a mark of villainy, from Uncle Andrew’s experiments on a guinea pig in The Magician’s Nephew to the Calormenes’ practice of enslaving talking horses in The Last Battle. Unfortunately, adults tend to stop reading books like these. They lose the childlike wonder at the natural world such stories nurture. Like Lewis’s imagined cynics and critics, they no longer see any value in reading about pert Nutkin or Rat the oarsman. And once so disenchanted, Lewis fears, indifference toward the sufferings of actual animals is possible.

Are there authors that awaken your affection for animals? Poetry or fiction that inspires compassion on their behalf? Books that so blur the boundaries between the imagination and reality that love “splashes” over onto the “Actual archtypes”? Read on. Sometimes we find wisdom and grace in the most unlikely places, “if we are not too proud to seek it.”

Michael Gilmour is Professor of New Testament and English Literature, Fellow of the Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics, Department Head of Biblical Studies & Practical Theology at Providence, University College, Canada. He is author of numerous theological works including Eden’s Other Residents: The Bible and Animals. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade, 2014.