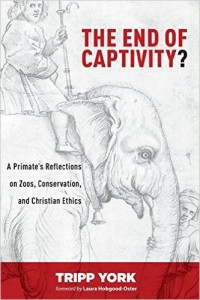

Dr Tripp York discusses his latest book, The End of Captivity?, which questions what keeping animals in captivity says about us; their captors.

You have spent hundreds of hours working with animals in captivity. How has this experience influenced and inspired the writing of your book?

It was important for me to experience, first-hand, working with animals in various forms of captivity. You learn far more about the needs of animals, as well as the work that goes into taking care of these animals, when you’re doing it yourself. The experience was crucial as there’s no way to replicate such knowledge by simply reading a handbook on, say, animal husbandry. I’m also, now, completely infatuated with sloths, giraffes, calimicos, and emerald boas. All of these creatures inspire me to do more for them. I’m even inspired by squirrel monkeys and gibbons—despite the fact that a squirrel monkey purposely pooped on me and gibbon peed on me!

It was important for me to experience, first-hand, working with animals in various forms of captivity. You learn far more about the needs of animals, as well as the work that goes into taking care of these animals, when you’re doing it yourself. The experience was crucial as there’s no way to replicate such knowledge by simply reading a handbook on, say, animal husbandry. I’m also, now, completely infatuated with sloths, giraffes, calimicos, and emerald boas. All of these creatures inspire me to do more for them. I’m even inspired by squirrel monkeys and gibbons—despite the fact that a squirrel monkey purposely pooped on me and gibbon peed on me!

What do you think the purpose for animals is and can it be realised for captive animals?

The purpose of animals depends upon the tradition in which you’re making such claims. For instance, in some branches of naturalism, the primary purpose of animals is procreation (for humans and non-humans). Contrast that with a religion such as Christianity that argues (whether Christians know this or not) that the primary purpose of animals is the glorification of the triune God. If nothing else, that’s certainly more of an interesting story than the one offered by some variations of naturalism (and, yes, that’s a reference to Life of Pi—which, as you well know, made a number of appearances in my book).

The beauty within the Animal Kingdom is doubtless awe-inspiring. How has this very beauty brought out the best and worst in humanity?

We are a very confused species when it comes to the rest of the animal kingdom. We love its beauty, at least in theory (sometimes in reality), yet we are hell-bent on destroying it. The Baconian in us wishes to master nature, while others understand that the world is never going to be more beautiful than it is right now. I think the latter are those people doing everything they can to tread softly. I like treading-softly. We should be soft-treaders.

The topic of captive animals is a complex one. What questions should a Christian ask themselves before visiting a zoo?

Ah, that’s a tough one. A few things anyone, Christian or not, should ask is, Why are these animals here? What (and whom) do they represent? What are you expecting to get out of your visit? Are you visiting for the mere sake of entertainment? You know, grab popcorn, soda, and take lots of photos? Or, are you there to learn something about as to why these animals are there and how that is connected to our ever-persistent desire to rid the world of all of its natural habitats? Those few questions should keep you busy for quite a while.

Ah, that’s a tough one. A few things anyone, Christian or not, should ask is, Why are these animals here? What (and whom) do they represent? What are you expecting to get out of your visit? Are you visiting for the mere sake of entertainment? You know, grab popcorn, soda, and take lots of photos? Or, are you there to learn something about as to why these animals are there and how that is connected to our ever-persistent desire to rid the world of all of its natural habitats? Those few questions should keep you busy for quite a while.

There are countless everyday examples of animals and humans forming strong bonds together. Could this be described as “reciprocal love” and what might this mean theologically?

For sure, though, to be honest, I’m more interested in non-reciprocal love between us and other species. It’s not that I’m not fascinated by all of the stories of hippos loving turtles, orangutans befriending elephants, and gorillas keeping kittens as pets, it’s just, when it comes to how we respond to other animals, I’m often more impressed by those people who love animals and expect nothing in return. (From a theological perspective, reciprocal love is not the highest form of love.) I often think about how, for example, Steve Irwin, a controversial figure in his own right, did everything he could to convince us to love the so-called ‘ugly’ animals of the world: crocodiles, reptiles, and scary spiders. Yet, he knew that, despite all of his efforts to make the world a more hospitable place for these creatures, it was unlikely that they would ever love him in return. It’s easy to love an animal that bonds with us, but try loving one that not only will not bond with you, but very well may attempt to kill you—even while you’re trying to save it. That’s impressive, and it takes a different sort of person to commit their lives to that kind of non-reciprocating love.

You underline the unavoidable interdependence of humans and animals. How can individual Christians and Church communities make a positive contribution to this relationship?

To quote my favorite punk rock band of all time, Propagandhi: “Stop consuming animals!” The absolute easiest way to make a positive contribution to animal relations, and to the earth, is to, at the bare-minimum, stop eating factory-farmed animals. Slaughterhouses are destroying our water, our soil, our trees, our air, our bodies, and the billions of nonhuman bodies treated as if they are just soulless machines designed for no other reason than to appease our gluttonous practices. Animals are not commodities. They are not here for us to maim, torture, and turn into human excrement. That’s a piss-poor account of creation, not to mention eschatology, if I’ve ever heard one. We lie when we call creation good while simultaneously destroying it with such complete and reckless abandon. So, you know, just stop participating in that system. It’s embarrassing. The world is watching, you know? And the best many Christians can say is that animals are here for us to systematically torture, brutalize, and consume so that they can be ultimately flushed down our toilets? That’s our theology of creation? Come on. Seriously. That’s just embarrassing.

To quote my favorite punk rock band of all time, Propagandhi: “Stop consuming animals!” The absolute easiest way to make a positive contribution to animal relations, and to the earth, is to, at the bare-minimum, stop eating factory-farmed animals. Slaughterhouses are destroying our water, our soil, our trees, our air, our bodies, and the billions of nonhuman bodies treated as if they are just soulless machines designed for no other reason than to appease our gluttonous practices. Animals are not commodities. They are not here for us to maim, torture, and turn into human excrement. That’s a piss-poor account of creation, not to mention eschatology, if I’ve ever heard one. We lie when we call creation good while simultaneously destroying it with such complete and reckless abandon. So, you know, just stop participating in that system. It’s embarrassing. The world is watching, you know? And the best many Christians can say is that animals are here for us to systematically torture, brutalize, and consume so that they can be ultimately flushed down our toilets? That’s our theology of creation? Come on. Seriously. That’s just embarrassing.

Tripp York, PhD, teaches in the Religious Studies Department at Virginia Wesleyan College in Norfolk, VA. He is the author and editor of a dozen books including, The Devil Wears Nada, Third Way Allegiance, and the three volume series, The Peaceable Kingdom. For further information, check out his website: http://trippyork.com

The End of Captivity? is now available in printed and Kindle versions.