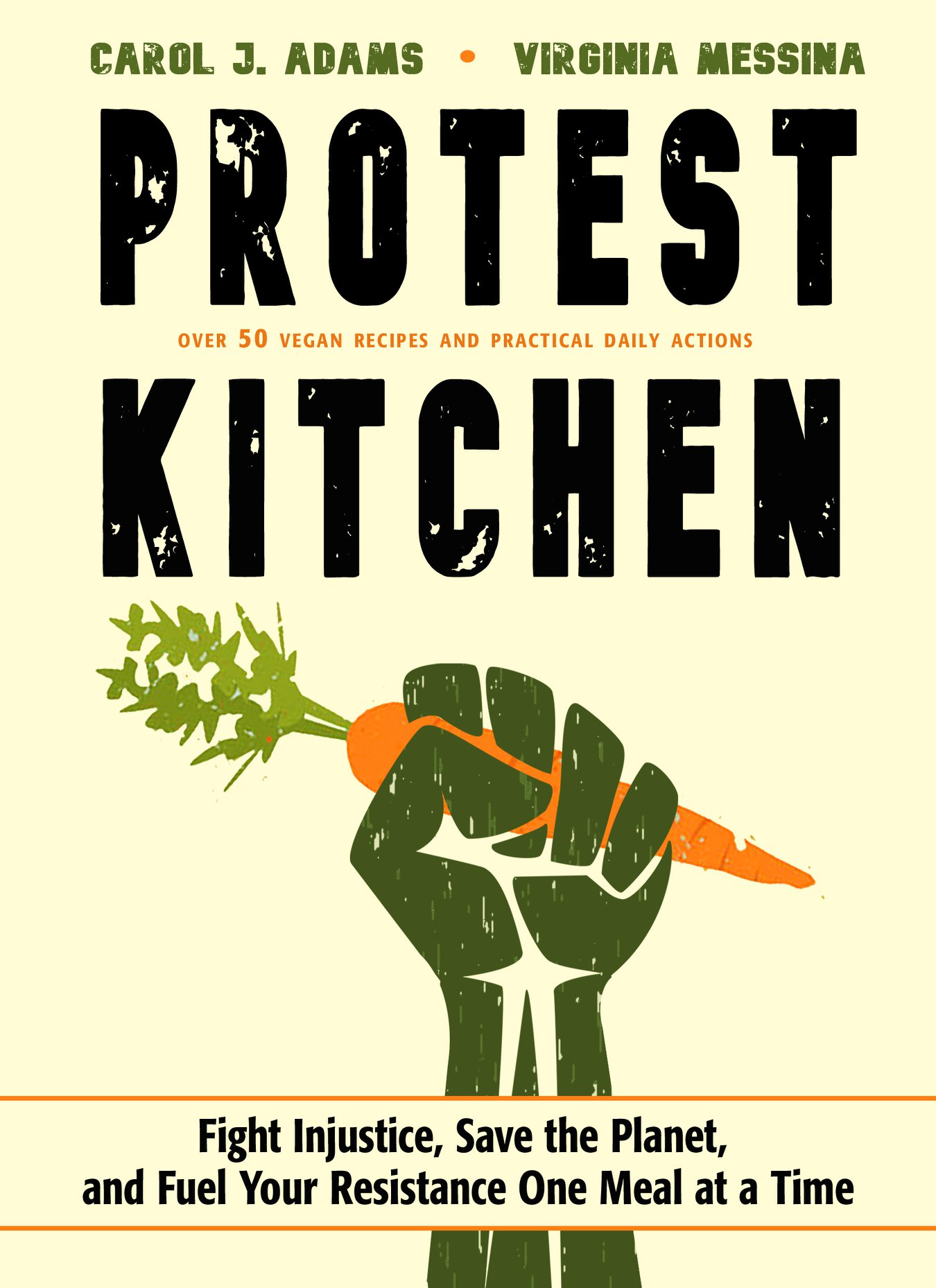

How can people fight injustice, save the planet, and fuel their resistance one meal at a time? Renowned animal rights advocate Carol J. Adams and vegan dietitian Virginia Messina explain how in their new book Protest Kitchen.

What is the message of Protest Kitchen?

How we eat is a social justice issue with far-reaching impacts. Food choices affect more than just personal health, animal welfare, and the environment. In Protest Kitchen, we present a case for the ethics and practice of veganism as an act of resistance and an important expression of progressive values. So many problems in the world occur when humans erect barriers of “otherness.” People who are involved in working against regressive politics are sensitive to this, but they may not realize that vegans have been concerned about this issue of “the other” for decades because animals are also “others.” Because of the work that vegans have been doing, we have both philosophical and practical tools in our toolkit that we can share with the resistance.

How we eat is a social justice issue with far-reaching impacts. Food choices affect more than just personal health, animal welfare, and the environment. In Protest Kitchen, we present a case for the ethics and practice of veganism as an act of resistance and an important expression of progressive values. So many problems in the world occur when humans erect barriers of “otherness.” People who are involved in working against regressive politics are sensitive to this, but they may not realize that vegans have been concerned about this issue of “the other” for decades because animals are also “others.” Because of the work that vegans have been doing, we have both philosophical and practical tools in our toolkit that we can share with the resistance.

In a nutshell, the book asks readers to consider that the ways we view and treat animals are related to other types of oppression and therefore tie in with efforts to resist regressive politics. This means that veganism, as a social justice movement, has a place within the broader context of the political resistance.

How can our kitchens act as a source of personal resistance?

A protest kitchen is a place where we make choices about food as a way that challenges regressive politics and a place where we enact the recognition that personal actions still matter, including what we eat day by day. The dairy and meat industries wouldn’t be concerned about what to call plant-based milk and plant-based meat unless the purchasing of these products is impacting their businesses. Their concern, and their desire to keep these names (“milk” and “meat”) to themselves illustrates our case—individual actions matter. In buying plant-based meat and plant-based milk, we are boycotting their “products” and it is cumulatively affecting their bottom line. Our protest kitchens continue the traditions of historic protest kitchens—boycotting and feeding people.

Can you say more about how veganism is a part of the resistance against contemporary cultural and political oppression?

Part of the message of our book is that the very nature of social justice recognizes how oppressions are interconnected and so resistance needs to be as well. Many people think that resistance is about how humans experience oppression. But our point is that we can’t understand the experience of oppression without looking on the other side of the species line and comprehending how the lives of animals are intertwined with ours. When we boycott animal foods, we are challenging a powerful industry that promotes misogyny [see for instance our article on how meat and milk uphold misogyny] and that exploits workers. Slaughterhouse workers—and those who clean up slaughterhouses—are vulnerable individuals, often undocumented workers, whose constant injuries make working in a slaughterhouse the most dangerous job in the United States. Animal agriculture as an industry uses its clout to employ tactics that undermine free speech as we see with Ag Gag laws that have been adopted in the United States.

Climate change affects poor people more than affluent people—and animal agriculture is a significant contributor to climate change. Choosing to eat a vegan diet is one way of witnessing against the harm that comes with climate change.

Climate change affects poor people more than affluent people—and animal agriculture is a significant contributor to climate change. Choosing to eat a vegan diet is one way of witnessing against the harm that comes with climate change.

Exploitation of animals demands that we make a decision about who deserves and doesn’t deserve fair treatment and this is a tactic that spills over into how we treat humans. Viewing disenfranchised humans as animals—calling them “beasts,” or “animals,” or “pigs”, etc.—is a way of using animality against humans. But we have to recognize how animality is always being used against animals, too. Animal exploitation is an expression of power and control, the same power and control that lie at the root of other types of exploitation. So a stance against using animals for food, entertainment, or clothing is a stance against the dominant culture of exploitation.

Would Jesus’ kitchen be a Protest Kitchen?

We know that Jesus fed people and multiplied food resources. He showed compassion to those humans who were seen as “others” during his time. Wherever Jesus went, compassion was a key aspect of his message.

It’s hard to imagine that Jesus would participate in a culture of eating that does so much damage to all of God’s creation and causes so much suffering. The Jesus of Matthew 25: 35-40 asks us to welcome the stranger, and the parable of the Good Samaritan suggests that the stranger or the “other,” is in fact our neighbor. Most likely Jesus would be a bigger fan of sanctuary cities than of the rallying cry to “build the wall.” The Jesus who counted women among his disciples and who cast aside the well-established boundaries between men and women would not support the racism and misogyny that are facets of oppressive politics. We think Jesus would embrace the values of the political resistance and would see that the principles at the foundation of that resistance are the same ones that lie at the foundation of veganism. The way of Jesus was a way of justice, mercy, compassion, and inclusiveness which are the same values that define a protest kitchen.

It’s hard to imagine that Jesus would participate in a culture of eating that does so much damage to all of God’s creation and causes so much suffering. The Jesus of Matthew 25: 35-40 asks us to welcome the stranger, and the parable of the Good Samaritan suggests that the stranger or the “other,” is in fact our neighbor. Most likely Jesus would be a bigger fan of sanctuary cities than of the rallying cry to “build the wall.” The Jesus who counted women among his disciples and who cast aside the well-established boundaries between men and women would not support the racism and misogyny that are facets of oppressive politics. We think Jesus would embrace the values of the political resistance and would see that the principles at the foundation of that resistance are the same ones that lie at the foundation of veganism. The way of Jesus was a way of justice, mercy, compassion, and inclusiveness which are the same values that define a protest kitchen.

If Jesus’s followers are eating dead animals, dairy, and eggs, they are reducing resources rather than multiplying them. But they are also actively supporting a food system that harms others—not only the animals, but all those who are hurt by the production of animal food: the vulnerable working in slaughterhouses, the vulnerable at risk of climate destruction because of where they live. In Protest Kitchen we state, “The most important mission trip a church can take is to go vegan.”

How might veganism empower today’s followers of Christ?

When did I see you working in a slaughterhouse? When did I see you living next to a factory farm with its manure swamps and toxic smells? When did I see you drowned by a storm made more intense by climate change? When did I see you slaughtered?”

How we eat can serve as a meaningful stance against injustice every day and an enaction of the message of Matthew 25. This in itself is empowering. It’s also empowering to know that you can shift your dietary choices to ones that reflect your values.

How we eat can serve as a meaningful stance against injustice every day and an enaction of the message of Matthew 25. This in itself is empowering. It’s also empowering to know that you can shift your dietary choices to ones that reflect your values.

Christian values include fairness, compassion and justice; meal preparation and food purchases provide a way to put those values into action three or more times a day. Vegan choices provide opportunity to put beliefs into action. This is a fundamental message of our book. You may not be able to get to Washington, D.C. or London or Berlin for a big protest and you may have limited time to volunteer and maybe you feel that your job doesn’t offer many chances to express your values. But your kitchen is a place where you do have an opportunity to express those values. You can always make a choice that doesn’t harm animals, uphold misogyny, or contribute to exploitation of workers or contribute more to global warming. It can be as simple as choosing to pour almond milk over your cereal instead of cow’s milk. It may seem like a small thing, but every choice like this is a remarkably potent expression of your values. Look at one of the messages of the shared liturgical value of Communion: We do not stop being Christians when we eat. But if we continue to eat meat, dairy, and eggs, we refute the Christian message of compassion and justice. We are not saying that going vegan is all that anyone needs to do. But for those who strive to live the values that were taught by Jesus, it is a part of living in communion with others.

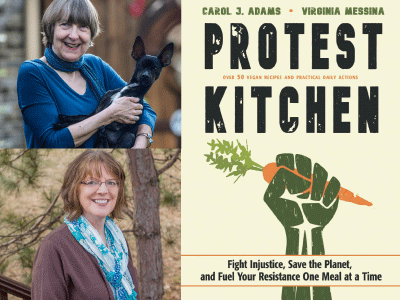

Carol J. Adams is a feminist-vegan advocate, activist, and independent scholar and the author of numerous books including her pathbreaking The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. For more information about Carol and her work, please see Carol’s website.

Carol J. Adams is a feminist-vegan advocate, activist, and independent scholar and the author of numerous books including her pathbreaking The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. For more information about Carol and her work, please see Carol’s website.

Ginny Messina MPH, RD is a vegan dietitian of over 30 years’ experience and author of numerous books on vegan nutrition. For more information on Ginny and her work, please see Ginny’s website.