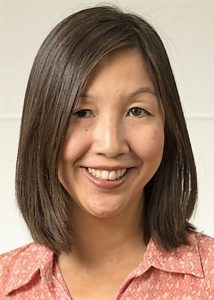

Grace Yia-Hei Kao, Associate Professor of Ethics at Claremont School of Theology, discusses faith, ecofeminism and how both men and women can example Christian ideals of love, peace and justice in favour of animals.

How did you first develop an interest in animal advocacy?

I’ve been concerned about animals, in one way or another and with greater and lesser degrees of intensity, throughout my life. When I was in kindergartener living in a suburb of Los Angeles, stray cats and dogs would turn-up with some regularity on our driveway. My brother and I would be moved at the sight of their scrawniness and would want to keep them permanently. Though we never could – we were only allowed to care for them for a few days before my parents would call animal control – those early experiences led to our family eventually coming to adopt a baby kitten from a family friend.

I’ve been concerned about animals, in one way or another and with greater and lesser degrees of intensity, throughout my life. When I was in kindergartener living in a suburb of Los Angeles, stray cats and dogs would turn-up with some regularity on our driveway. My brother and I would be moved at the sight of their scrawniness and would want to keep them permanently. Though we never could – we were only allowed to care for them for a few days before my parents would call animal control – those early experiences led to our family eventually coming to adopt a baby kitten from a family friend.

When I was sixteen, I read Frances’ Moore Lappé’s now-classic Diet for a Small Planet, was totally convinced by her argument, and became a lacto-ovo vegetarian. While I didn’t then connect vegetarianism to animal welfare or rights, the idea that eating was a political act has stayed with me ever since. About a decade later as I turned to human rights theory in my dissertation and first book, I started to see intellectually that the theoretical foundations for human rights could—and arguably should—be expanded to cover the case of nonhuman animals.

In short, as philosopher Tom Regan has noted, there is a sense in which I was converted to animals for reasons of both “head” and “heart.”

Do women have a distinctive voice in speaking up for animals?

That’s a tough question! I would say both “yes” and “no.” I believe that ecofeminism—feminist theory and activism informed by ecology—has something distinctive to say about animals, but that both men and women can provide ecofeminist perspectives or analyses. Simply put, ecofeminism explores the many connections that can be found between women and nonhuman nature, be they linguistic (e.g., barrenness describes both “undesirable” land and women), cultural-symbolic (e.g., nature is commonly feminized and women animalized), historical (i.e., patriarchal systems have valorized men over both women and nonhuman nature), or religious (e.g., Adam was given the power in the Bible to name both woman (Eve) and the animals).

That’s a tough question! I would say both “yes” and “no.” I believe that ecofeminism—feminist theory and activism informed by ecology—has something distinctive to say about animals, but that both men and women can provide ecofeminist perspectives or analyses. Simply put, ecofeminism explores the many connections that can be found between women and nonhuman nature, be they linguistic (e.g., barrenness describes both “undesirable” land and women), cultural-symbolic (e.g., nature is commonly feminized and women animalized), historical (i.e., patriarchal systems have valorized men over both women and nonhuman nature), or religious (e.g., Adam was given the power in the Bible to name both woman (Eve) and the animals).

Today, it’s been said that women animal advocates outnumber men. There may be many reasons to explain this, but one that I haven’t favored is the view that women are “naturally” more caring, compassionate, or merciful (i.e., gender essentialism).

Is there a link between faith, feminism and animal advocacy?

There certainly can be. For me, my (eco)feminist and Christian commitments have commonly run together, whether we are talking about why I am a pacifist, generally buy second-hand clothes (vs. something new) as a form of recycling and to reduce my complicity in sweatshop labor, or eat a primarily plant-based diet as part of environmental stewardship. It’s similar with respect to animal advocacy. My Christianity teaches me about our common creatureliness and the need for us to attend to the “least of these.” And my ecofeminism likewise shows me how the fate of women and nonhuman animals are linked under patriarchy and thus how we must not attempt to elevate the status of women by denigrating what we share with other animals.

There certainly can be. For me, my (eco)feminist and Christian commitments have commonly run together, whether we are talking about why I am a pacifist, generally buy second-hand clothes (vs. something new) as a form of recycling and to reduce my complicity in sweatshop labor, or eat a primarily plant-based diet as part of environmental stewardship. It’s similar with respect to animal advocacy. My Christianity teaches me about our common creatureliness and the need for us to attend to the “least of these.” And my ecofeminism likewise shows me how the fate of women and nonhuman animals are linked under patriarchy and thus how we must not attempt to elevate the status of women by denigrating what we share with other animals.

Of course, in acknowledging the ways that my feminist Christianity has informed my animal advocacy, I do not want to suggest that animal advocacy must be grounded in an explicitly Christian or other religious manner in order either to be authentic or effective.

Do men suffer from shame in considering female and animal exploitation? What can they do to tackle injustice?

In contexts where one’s masculinity is rendered suspect if one does not display dominance over women and other animals, perhaps this is the case. But being against either the oppression of women or wanton cruelty toward animals should not be seen as gendered affair, but instead as something that common decency minimally requires. I recognize, however, that what is considered emasculinating will vary from one culture to the next.

How can Christians, men and women alike, bring about positive change in their lives and communities?

We all have different callings. Not all of us will be marching in protests or engaging in acts of civil disobedience, as the great teacher and mystic Howard Thurman reminds us. As Christians, however, we must all bear witness to the truth, so one thing we could all do is seek to discover and then disseminate it, which is to say that we will have to interrogate what marketing, industry, the media, and so forth tells us. Websites like Sarx and the Faith Outreach program of the Humane Society of the U.S. can certainly help with that. Next, the particular ways we individually or corporately work for Christian ideals—of love, peace, justice, and reconciliation—will vary according to our gifts, passions, temperament, and circumstances.

We all have different callings. Not all of us will be marching in protests or engaging in acts of civil disobedience, as the great teacher and mystic Howard Thurman reminds us. As Christians, however, we must all bear witness to the truth, so one thing we could all do is seek to discover and then disseminate it, which is to say that we will have to interrogate what marketing, industry, the media, and so forth tells us. Websites like Sarx and the Faith Outreach program of the Humane Society of the U.S. can certainly help with that. Next, the particular ways we individually or corporately work for Christian ideals—of love, peace, justice, and reconciliation—will vary according to our gifts, passions, temperament, and circumstances.

For instance, my area of influence is in the classroom and academy. I regularly teach a course entitled “Animal Theology and Ethics.” It’s subtitled “Rethinking Human-Animal Relationships” because I absolutely believe that ideas have consequences — that what we think theologically or philosophically about animals will affect the ways we go about treating them. I’ve been active in my professional societies in efforts to promote scholarly discourse on animals for similar reasons. I’m still discerning what other ways I could serve and show solidarity with our fellow creatures.

Dr. Grace Yia-Hei Kao is Associate Professor of Ethics, and Co-Director of the Center for Sexuality, Gender, and Religion at Claremont School of Theology. She is the author of Grounding Human Rights in a Pluralist World (2011), and co-editor of Asian American Christian Ethics (2015). She currently serves on the steering committee of the “Animals and Religion Group” of the American Academy of Religion and is the co-founder of the Animal Ethics Interest Group at the Society of Christian Ethics/Society of Jewish Ethics/Society for the Study of Muslim Ethics. For more information about her academic background or work, please click here or consult her personal website.