Andrew Knight is a Professor of Animal Welfare and Ethics at the University of Winchester, and Director of Research and Education for SAFE in New Zealand. He investigates the case of Jack the Ripper and posits whether he might have been a 19th century slaughterhouse worker. Andrew goes on to highlight the links between violence inflicted on animals, and that which is perpetrated on humans.

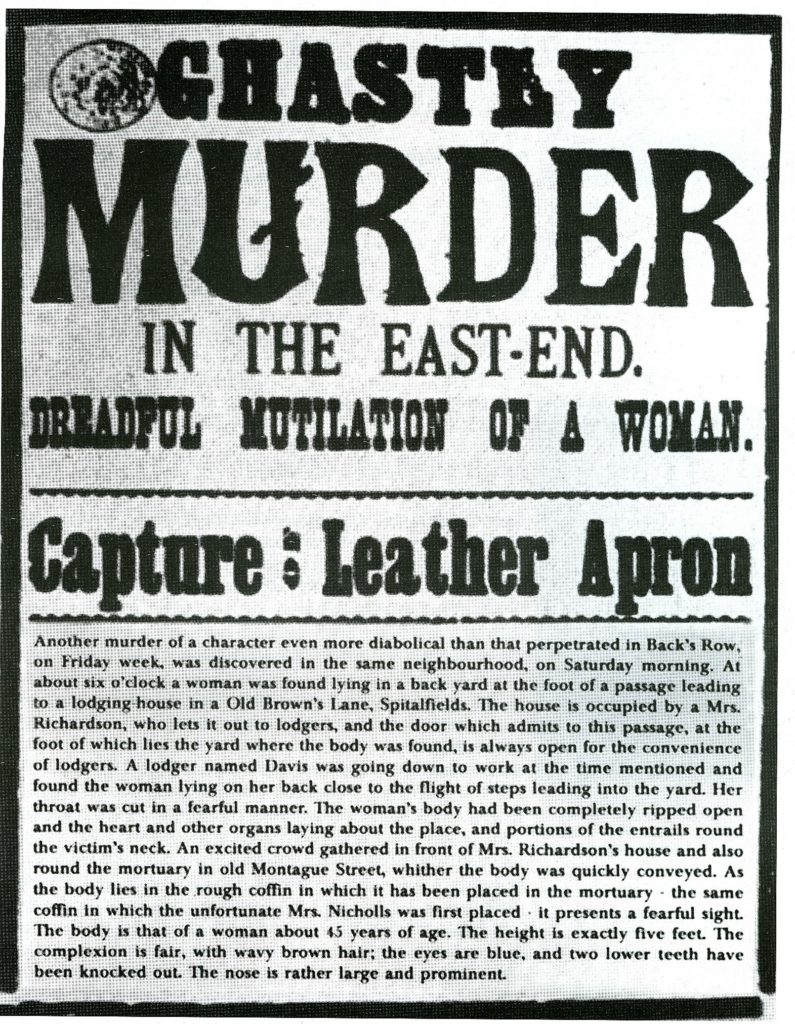

Life in 19th century London was harsh. Workers’ rights were a futuristic fantasy, and those lucky enough to have employment commonly worked both day and night. Cart driver Charles Cross was one of those ‘fortunate’ souls. At around 03:40 AM on 30 August 1888, whilst en route to work, Cross spied a body in front of a gated stable entrance [1] (p. 27). A speedily summoned surgeon estimated that prostitute Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols had been murdered just 10 minutes previously. Her throat had been twice cut, and her abdomen savagely mutilated, by a series of violent, jagged incisions [1] (pp. 35, 47). Although unaware at the time, those present were witnessing what would subsequently be considered the first murder of the world’s most infamous serial killer—Jack the Ripper.

Life in 19th century London was harsh. Workers’ rights were a futuristic fantasy, and those lucky enough to have employment commonly worked both day and night. Cart driver Charles Cross was one of those ‘fortunate’ souls. At around 03:40 AM on 30 August 1888, whilst en route to work, Cross spied a body in front of a gated stable entrance [1] (p. 27). A speedily summoned surgeon estimated that prostitute Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols had been murdered just 10 minutes previously. Her throat had been twice cut, and her abdomen savagely mutilated, by a series of violent, jagged incisions [1] (pp. 35, 47). Although unaware at the time, those present were witnessing what would subsequently be considered the first murder of the world’s most infamous serial killer—Jack the Ripper.

In the following 10 weeks four local women would share Polly’s fate. All were prostitutes, living and working in the impoverished East London slums, and all but one had their throats cut prior to abdominal mutilation. All efforts by the London constabulary, and subsequently, local vigilantes, to identify the killer, remained fruitless, and a climate of fear descended upon the city. The extraordinary brutality of the murders, combined with the enduring mystery of the killer’s identity, resulted in a fascination with the case that remains strong to this very day.

Could Jack have been a slaughterman?

Over 100 theories about Jack’s identity exist, ranging from the credible to the bizarre. However, as described in our detailed study recently published in Animals [2], multiple factors combine to create a remarkably compelling theory that he was very probably a local slaughterhouse worker. Numerous small-scale slaughterhouses existed in East London in the 1880s.

Over 100 theories about Jack’s identity exist, ranging from the credible to the bizarre. However, as described in our detailed study recently published in Animals [2], multiple factors combine to create a remarkably compelling theory that he was very probably a local slaughterhouse worker. Numerous small-scale slaughterhouses existed in East London in the 1880s.

First, careful examination of a mortuary sketch of one of Jack’s victims reveal several aspects of incisional technique highly inconsistent with professional surgical training. The main abdominal cuts appear to have proceeded in the wrong direction, and their degree of raggedness exceeds that which would be probable in any person possessed of even minimal surgical skill, even when working under conditions of haste and poor light. And yet, in that poor light, with his victims awkwardly positioned at ground level, rather than on a dissecting table, Jack nevertheless successfully located and appropriated certain specific internal organs, with a speed that would have put most medical students to shame.

At the autopsy of Catherine Eddowes (Jack’s fourth victim) Phillips and Brown – the examining pathologist, and police surgeon, respectively – found that the injuries could have been inflicted by a person who had been a hunter, butcher, slaughterman, or a qualified or student surgeon [3] (p. 208). However, Jack also speedily dispatched his victims with full thickness throat incisions, extending nearly ear to ear. This is the main technique commonly used both historically and contemporaneously, to kill and bleed out land animals intended for human consumption.

Jack was also able to swiftly overpower and dispatch multiple victims, in close proximity to streets that were busy even during the early hours of the night – yet never a sound was heard. Such strength would have been necessary for, and induced by, the physical nature of the work in the slaughterhouses of this era. As described in the Birmingham Daily Post, “. . . a slaughterhouse is at its best but a chamber of horrors . . . in which oxen and sheep become beef and mutton under the hands of the brawny, half-naked pole-axing men” [4]. Half-naked, no doubt, because of the hard physical labour involved, and the exercise-induced body temperature increases and sweating.

Jack was also able to swiftly overpower and dispatch multiple victims, in close proximity to streets that were busy even during the early hours of the night – yet never a sound was heard. Such strength would have been necessary for, and induced by, the physical nature of the work in the slaughterhouses of this era. As described in the Birmingham Daily Post, “. . . a slaughterhouse is at its best but a chamber of horrors . . . in which oxen and sheep become beef and mutton under the hands of the brawny, half-naked pole-axing men” [4]. Half-naked, no doubt, because of the hard physical labour involved, and the exercise-induced body temperature increases and sweating.

Slaughterhouses and violent crime

Conditions in historical slaughterhouses for both animals and workers were exceedingly harsh. Modern slaughterhouses have become vaster, more impersonal, industrialised systems of killing, within which systematic animal abuse continues. Since 2009, British animal advocacy organization Animal Aid has covertly filmed within 12 randomly chosen British slaughterhouses. Cruelty and law breaking were rampant in 11 out of 12. Animals were kicked, slapped, stamped on, hoisted by fleeces and ears, and thrown into stunning pens. They were improperly stunned and killed, including by throat-cutting, while still conscious. Some were deliberately beaten, and pigs were burnt with cigarettes [5]. With more than 70 billion terrestrial animals slaughtered annually by 2013 (the most recently reported year, by April 2017) [6], slaughterhouse abuse is one of the greatest animal welfare concerns today.

Additionally, modern sociological research has highlighted clear links between violence towards animals, and that perpetrated on humans. To some degree, this is understandable – even inevitable – for slaughterhouse workers. If they allowed themselves to feel appropriate sympathy and concern for the animals, given their status as sentient beings who experience fear, pain and stress, and who do not wish to die, it would interfere with their abilities to fulfil the roles required of them, and hence, their economic survival. As noted by Dillard [7], “By habitually violating one’s natural preference against killing, the worker very likely is adversely psychologically impacted”.

Additionally, modern sociological research has highlighted clear links between violence towards animals, and that perpetrated on humans. To some degree, this is understandable – even inevitable – for slaughterhouse workers. If they allowed themselves to feel appropriate sympathy and concern for the animals, given their status as sentient beings who experience fear, pain and stress, and who do not wish to die, it would interfere with their abilities to fulfil the roles required of them, and hence, their economic survival. As noted by Dillard [7], “By habitually violating one’s natural preference against killing, the worker very likely is adversely psychologically impacted”.

Particularly disturbing are significant increases in the most violent crimes in communities surrounding slaughterhouses. After analysing 1994–2002 data from 581 U.S. counties, Fitzgerald and colleagues [8] reported that total arrest rates, and arrests for violent crimes, rape and other sex offenses, were increased among slaughterhouse workers. Particularly noteworthy were increases in sexual assault rates. Offences included sexual attacks on males, incest, indecent exposure, statutory rape, and “crimes against nature”. As noted, “Increases in slaughterhouse employment had a significant positive effect on rape arrests across the entire time period under study” (p. 174).

After analysing 2000 data from 248 U.S. counties, Jacques [9] similarly found that slaughterhouse presence corresponded with a 22% increase in total arrests, a 90% increase in offenses against the family, increased aggravated assaults, and a 166% increase in arrests for rape. In East London in the 1880s, such effects may very well have contributed to the creation of the world’s most infamous serial killer. Given dramatic modern increases in numbers of animals slaughtered, they should hardly be of lesser concern today.

After analysing 2000 data from 248 U.S. counties, Jacques [9] similarly found that slaughterhouse presence corresponded with a 22% increase in total arrests, a 90% increase in offenses against the family, increased aggravated assaults, and a 166% increase in arrests for rape. In East London in the 1880s, such effects may very well have contributed to the creation of the world’s most infamous serial killer. Given dramatic modern increases in numbers of animals slaughtered, they should hardly be of lesser concern today.

It may once have been necessary to kill other sentient creatures in order to survive. Such excuses no longer have any merit, and indeed, the modern business of animal slaughter profoundly harms the animals abused and killed, the workers required to kill them, and even their surrounding communities. It undeniably harms consumers whose health is damaged by overconsumption of animal products [10-11]. It is clearly time to end our destructive social dependence on industrialised animal slaughter.

Professor Andrew Knight MANZCVS, DipECAWBM (AWSEL), DACAW, PhD, FRCVS, SFHEA is the Founding Director of the University of Winchester Centre for Animal Welfare, and established its MSc Animal Welfare Science, Ethics & Law. For more information about this programme, click here.

References

- Evans, S.P. and Skinner, K. (2000). The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. London: Constable and Robinson.

- Knight, A. and Watson, K.D. (2017). Was Jack the Ripper a slaughterman? Human-animal violence and the world’s most infamous serial killer. Animals7, 30. http://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/7/4/30, accessed 26 Jun. 2017.

- Evans, S.P. and Skinner, K. (2002). Jack the Ripper and the Whitechapel Murders; Document Pack. Kew, UK: PRO Publications.

- Anonymous (1888). The meat supply of London. Birmingham Daily Post, 24 December 1888: 7.

- Animal Aid (2016). The “Humane Slaughter” Myth. http://www.animalaid.org.uk/h/n/CAMPAIGNS/slaughter/ALL///, accessed 27 Jun. 2017.

- Food and Agriculture of the United Nations (2017). FAOSTAT (Database): Livestock Primary (2017). http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QL, accessed 03 Apr. 2017.

- Dillard, J. (2008). A slaughterhouse nightmare: psychological harm suffered by slaughterhouse employees and the possibility of redress through legal reform. Georget. J. Poverty Law Policy 15: 391–408.

- Fitzgerald, A.J., Kalof, L. and Dietz, T. (2009). Slaughterhouses and increased crime rates: an empirical analysis of the spillover from “The Jungle” into the surrounding community. Organ. Environ. 22: 158–184.

- Jacques, J.R. (2015). The slaughterhouse, social disorganization, and violent crime in rural communities. Soc. Anim. 23: 594–612.

- Walker, P., Rhubart-Berg, P., McKenzie, S., Kelling, K. and Lawrence, R.S. (2005). Public health implications of meat production and consumption. Public Health Nutr 8: 348-356.

- Sinha, R., Cross, A. J., Graubard, B. I., Leitzmann, M. F., & Schatzkin, A. (2009). Meat intake and mortality: a prospective study of over half a million people. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(6): 562-571.