Mary Colwell, public speaker, producer and writer specialising in nature and the environment, reflects upon Thomas Merton, God’s presence within creation and humanity’s connection with the natural world.

Mary Colwell, public speaker, producer and writer specialising in nature and the environment, reflects upon Thomas Merton, God’s presence within creation and humanity’s connection with the natural world.

Everyone can spend time alone, simply being in the world. It requires nothing other than time, a mind willing to be calm and a heart that searches for truth. As I write this, in the centre of a city with the constant drone of traffic, I can be alone with a robin as it sings in a tree. I can concentrate on the complexity and purity of the sound, so loud and clear from such a small creature. Each phrase is different, the pauses vary in length, the volume rises and falls at different times. I can wonder at the varied pattern of the bark of the tree and the shapes of the leaves. The branches hold solidity in their twisted form that is unique to this particular tree. There is no other in the world like it, no other robin such as the one before me. I am presented with individuality and richness enough for hours of contemplation. With a little practice, the human world fades and I am present only to the untameable and natural. In my own small way I am following in the footsteps of the giants of Christian contemplation.

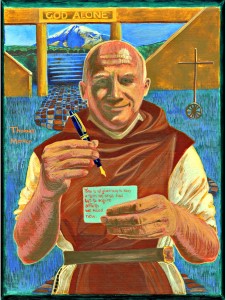

Thomas Merton, the towering mystic and hermetic monk, is known for many spiritual insights, but his relationship with nature is less talked about. Through his long hours of silence in the woods of Kentucky he found God’s vastness revealed in the smallest details of the life that surrounded him. God “speaks to us gently in ten thousand things…he shines not on them but within them.” These “things,” the birds, trees and flowers of the wood, shine with an individual identity that reflect God in countless nuanced ways. They are whole within and of themselves and the subtly of difference we perceive between them is a living language speaking of the divine. Therefore, there is no one ideal being, no perfect blackbird or oak tree, or human – all reflect an innate and unique holiness. The Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins called this “inscape,” a term Merton adopts, “their inscape is their sanctity.”

Thomas Merton, the towering mystic and hermetic monk, is known for many spiritual insights, but his relationship with nature is less talked about. Through his long hours of silence in the woods of Kentucky he found God’s vastness revealed in the smallest details of the life that surrounded him. God “speaks to us gently in ten thousand things…he shines not on them but within them.” These “things,” the birds, trees and flowers of the wood, shine with an individual identity that reflect God in countless nuanced ways. They are whole within and of themselves and the subtly of difference we perceive between them is a living language speaking of the divine. Therefore, there is no one ideal being, no perfect blackbird or oak tree, or human – all reflect an innate and unique holiness. The Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins called this “inscape,” a term Merton adopts, “their inscape is their sanctity.”

We can get a sense of the contemplative Merton as he prays in the depths of the night, accompanied only by the music of the wind in the trees and the calling of night creatures. His words are intense and beautiful.

“…I live in the woods out of necessity. I get out of bed in the middle of the night because it is imperative that I hear the silence of the night alone, and, with my face on the floor, say psalms, alone, in the silence of the night.

It is necessary for me to live here alone without a woman, for the silence of the forest is my bride, and the sweet dark warmth of the whole world is my love, and out of the heart of that dark warmth comes the secret that is heard only in silence, but it is the root of all the secrets that are whispered by all the lovers in their beds all over the world.”

Dancing in the water of Life: The Journals of Thomas Merton Vol V

Thomas Merton spent his whole life as a monk listening to the voice of God whispering secrets in every living being.

For, like a grain of fire

Smouldering in the heart

Of every living essence

God plants His undivided power –

Buries His thought too vast

For worlds

In seeds and roots and blade

And flower.

The Sowing of Meanings

If God is truly present in nature in this way, and I believe He is, then taking steps to protect it from destruction is not an onerous duty but a passion that overwhelms. As precious individual creatures succumb to the relentless pressures of the modern world, as species after species fall prey to humanity’s activities, it would be a poor Christian that simply let it happen. Taking action to protect the natural world is, to my mind, a Christian imperative. There are many demands on our time and generosity, but this cannot be a lesser cause. Nature provides us with the inspiration for deep prayer and insight; it speaks everyday of God. And of course, no matter who we are, what colour or creed, we all need the natural world simply to stay alive.

If God is truly present in nature in this way, and I believe He is, then taking steps to protect it from destruction is not an onerous duty but a passion that overwhelms. As precious individual creatures succumb to the relentless pressures of the modern world, as species after species fall prey to humanity’s activities, it would be a poor Christian that simply let it happen. Taking action to protect the natural world is, to my mind, a Christian imperative. There are many demands on our time and generosity, but this cannot be a lesser cause. Nature provides us with the inspiration for deep prayer and insight; it speaks everyday of God. And of course, no matter who we are, what colour or creed, we all need the natural world simply to stay alive.

It is easy to feel overwhelmed by the task and therefore vital to remember that we are not being asked to save everything alone. All of us can only do what we can, be that small or large. But as long as it is done with true and wholehearted commitment, then we will act well. Do one thing and do it well need not merge into multi-tasking where many things can be done badly and which sap us of energy. We are simply asked for our best. I often say the final words of A Step Along the Way, a poem written for Archbishop Oscar Romero:

We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of liberation in realizing that.

This enables us to do something, and to do it very well.

It may be incomplete, but it is a beginning, a step along the way, an

opportunity for the Lord’s grace to enter and do the rest.

We may never see the end results, but that is the difference between the master builder and the worker.

We are workers, not master builders; ministers, not messiahs.

We are prophets of a future not our own

On April 21st I set out on a 500 mile walk to raise awareness about the decline of the curlew, our largest wading bird with a bubbling, evocative call. This is my one task and I hope to do it well. A world without the curlew would be depleted and impoverished. Thomas Merton called individual creatures “a thought of God,” and so this is my way of honouring those thoughts, hopefully helping keep them on our islands to inspire others for generations to come.

Mary Cowell is a producer and writer specialising in nature and the environment.

To check out her articles, radio, TV and internet productions: www.curlewmedia.com

To sponsor Mary’s 500 mile walk for curlews, please click here