A pangolin. These delightfully curious ant-eating scaled mammals are sometimes called ‘walking artichokes.’ Any animal that’s armoured, timid, nocturnal and lives in burrows, strikes me as one that is content to mind its own business.

Yet, tragically, pangolins are the most sought-after mammal for trafficking. Supposed magical properties drive demand for their foetuses, organs and scales in traditional medicines treating conditions as mundane as acne to the more bizarre of possession by ogres! Atop that, the elite show off their status and wealth by dining on such ‘delicacies’ as whole pangolin pickled in rice wine, foot-long tongue soup, and – to vouch for authenticity – pangolins are brought to restaurant customers’ tables alive, their throats cut and their blood drained to be drunk as an aphrodisiac.

No surprise then, that as an elusive species with a slow reproductive cycle, the humble pangolin is on the critically endangered list.

Beelzebub. Or, a literal translation, ‘Lord of the Flies’; the name of a post-war novel about a group of British boys stranded on an island.

Beelzebub. Or, a literal translation, ‘Lord of the Flies’; the name of a post-war novel about a group of British boys stranded on an island.

The dark tale emerges as a pessimistic commentary on the human condition and civilisation, exploring tensions between order and savagery, society and individualism, power and peace. The boys – all well off, educated, gifted – start well. They appoint leaders, agree to have fun, to survive and to keep a fire alight to signal their presence to passing ships. Eventually, however, their crisis overwhelms them. Group order is overturned by factions, survival becomes warped by paranoia, and the fire goes out. They descend into chaos and savagery.

The story reflects much about a post-war culture reeling in the wake of Nazism; a cultural soul-searching which sought to answer the question of whether the ideologies and associated atrocities of WW2 were an historic anomaly, never to be a witnessed again, or if, given certain conditions, history could repeat itself.

This social-psychological introspection wasn’t just focused on society at large, but on the individual. Could we – even we the assumed-to-be-civilised British and American people – ever do the same? Lord of the Flies serves as a mirror to the self; forcing us to squint at the ‘potential savage’ in our reflections.

St Benedict. ‘Listen carefully… to the master’s instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart.’ So begins The Rule of Saint Benedict. Listening, he says, brings us back to the God from whom we’ve drifted. Listening wakes us up to ‘the light that comes from God’ and the ‘voice that comes from heaven’; softening our hearts and showing us the way to life.

In Benedictine spirituality, listening is obedience. For a culture which elevates the self and personal freedom to the highest reference point of identity and value, an ethic of obedience seems at best countercultural and at worst dangerously outmoded. But as Wil Derske notes in his book Spirituality for Daily Life, Benedictine obedience isn’t ‘the end of personal freedom, but a beginning point of liberation: the cracking of the think crust around my “I” and the orienting of myself to who or what has something to say to me.’

Obedience is being attentive to that which is other-than-me; the yielding of conceit and the openness that something or someone may be saying something to me which requires both my attention and my loving response. That someone, or something, may be speaking in a voice that comes from heaven; from the very heart of God.

The question tying these three things together is: who are we in a crisis?

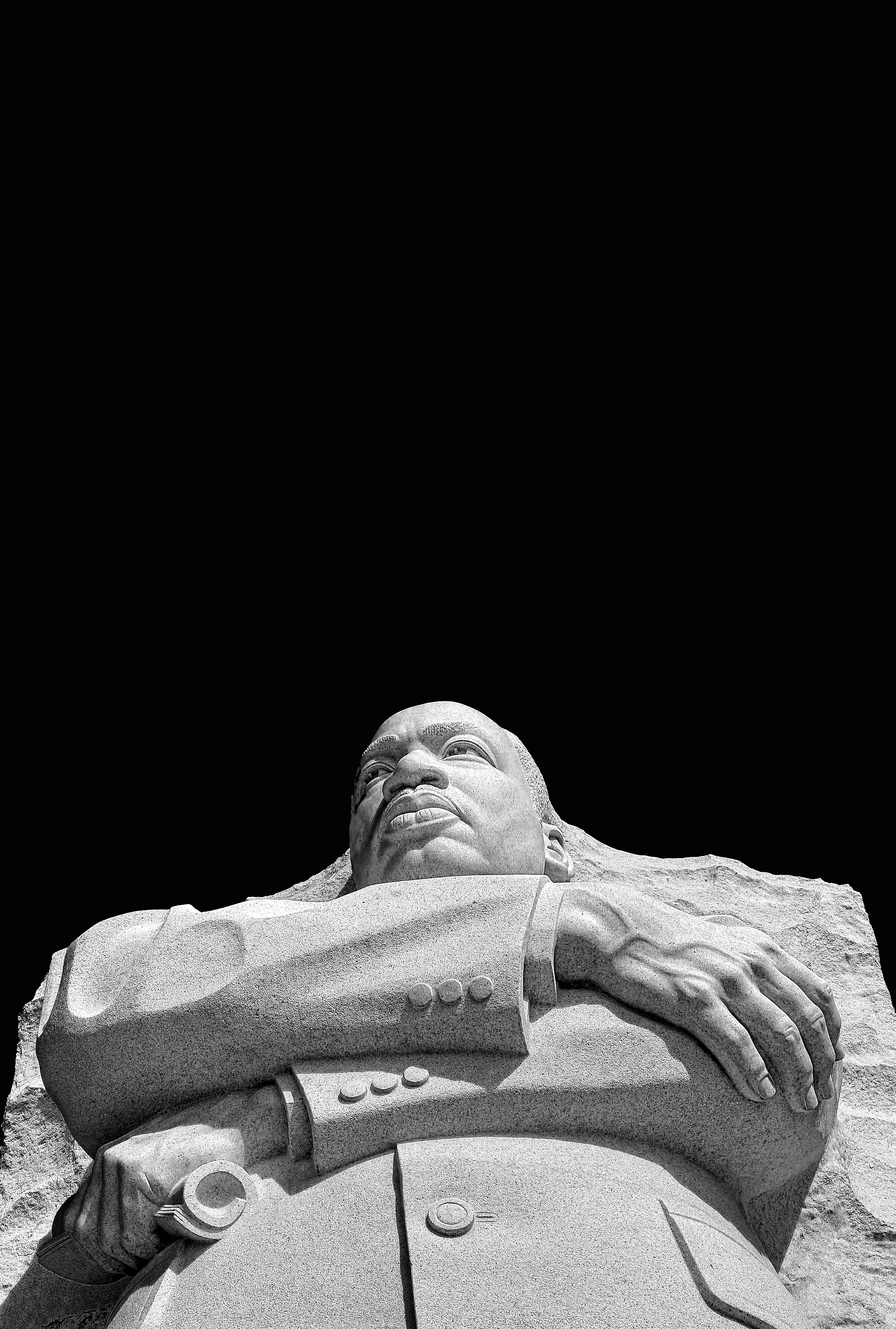

Because who we are in a crisis, may reveal who we truly are. As Martin Luther King Jr. is credited as saying:

Because who we are in a crisis, may reveal who we truly are. As Martin Luther King Jr. is credited as saying:

The ultimate measure of a (wo)man is not where (s)he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where (s)he stands at times of challenge and controversy.

Crisis exposes our defaults. The Covid-19 crisis is a bit-part in the bigger drama of how we have lived in God’s creation. And part of that unfolding drama is the story of our relationship with animals. This has come into sharp focus on pangolins because of speculation they could be the source of this particular coronavirus.

If we’re all ‘potential savages’ as Lord of the Flies suggests, then our default setting in a crisis would be ‘each one for themself.’ We respond to a crisis by dismissing, blaming or eliminating the ‘other’, asserting our own needs above the group, and denying our personal and shared responsibility and culpability.

The alternative is to listen; to recognise humbly that this crisis didn’t just ‘happen’ at the point it hit the headlines. Human activity has facilitated it. Such a deeply unsettling reality is of tremendous spiritual value if we open ourselves up to truly listening and responding to what this moment is saying to us.

We are being drawn to a new attentiveness in our relationship with all ‘others’ in creation, particularly animals. We are being woken up to our defaults, having a mirror held up to how we have been in the world that has led to the unnecessary suffering and death of countless animals: air and water pollution, ocean plastics, hunting for sport, wildlife habitat encroachment, deforestation, pesticides, over-consumption, experimentation and industrialised farming. And so on and on – for as long as we close the ears of our hearts to the groans of creation.

We are being called to a more loving response – to relate to animals and the wider creation within an evolved ethical framework that has at its heart the reality that we are of the same beloved creation as all ‘others’. This crisis isn’t a time to be ‘everyone for themselves’, but an opportunity to be woken by ‘the light that comes from God’ and to listen to the ‘voice of heaven’ leading us to life – a life of mutual flourishing for all.

The Revd Janey Hiller is an Ordained Minister and Pioneer Activist in the Anglican Diocese of Bristol.

The Revd Janey Hiller is an Ordained Minister and Pioneer Activist in the Anglican Diocese of Bristol.