Somerset-based animal rights artist, Philip McCulloch-Downs, explains the message behind his powerful and provocative artwork.

Tell us a bit about yourself and when you started painting

I’ve been painting and drawing all my life, very single-mindedly pursuing my creative urges, from my earliest years of dinosaurs and spaceships, to my polytechnic years of large scale cityscapes, to my recent animal rights campaigns.

What is an animal rights artist? How did you become one?

Following my illustration degree (from Leicester Poly) I worked in graphic design and continually created paintings and models, but without any real sense of purpose. This lasted about a decade, and then I decided I needed to add value and meaning to my life, and so I began volunteering at a local animal rights charity. This immediately affected the subject matter of my personal artwork, and for the next decade I indulged in writing and illustrating imaginative novels that addressed the issues of animal rights, human greed, overpopulation, pollution, etc. It was one of these illustrations that unexpectedly became the catalyst for all that I now do. This life-changing painting was for a short story about the future of the meat industry, and it was called ‘The Ghost Camera’. I decided to use the animal rights photographer Jo-Anne McArthur as the central figure in the piece, as she had been the inspiration behind the story. She is one of the heroes of the AR movement, and I wanted to send her the portrait as a surprise gift. When I did, Jo was moved to tears, posted the image on social media and this unleashed a wave of praise and support from thousands of people. I was dumbstruck! In a single moment all my painting practice, writing skills, knowledge of animal rights issues, and vegan life choices suddenly combined together. The decision was easy to make, it felt completely right.

What message do you wish to communicate?

My series of uncompromising paintings ‘Moving Pictures’ attempts to dignify the farm animals we exploit, by bearing witness to their suffering. I record their situation within the appalling world of factory farming, and I portray each individual creature with accuracy, empathy and compassion. Whereas people will often look away from photographs of disturbing and barbaric scenes, when they are presented as art, the viewer has an entirely different relationship with the image. They have a far better chance than photographs of intriguing the viewer and drawing them in. The horror is safely encased in a medium that works as a ‘filter’ between reality and the viewer, and if my work can catch and hold the attention, then hopefully empathy will follow, as well as the openness to learn more about the work.

Put simply, I want to confront the viewer with the truth. I want my art to bring the hidden individuals out of the darkness of their sheds, farrowing crates, concrete stalls, and airless barns, out into the light.

How have others reacted when they see your work?

Predictably, I’ve had an overwhelming positive response from vegan/AR people, and my work has been used by many charities as t-shirts, bags, banners, magazines etc. The sane response to some of the worst images is to cry, and I’ve had that reaction many times too. I’ve had criticism from just a few ‘anti-vegans’ on social media, but their reasoning is always illogical and they quickly reveal themselves to be attacking me out of deep-rooted feelings of guilt, or an unwillingness to face up to a reality that they are complicit in. I rarely engage in arguments though, as I want my work to speak for itself. The art should be eloquent enough to withstand any attempt to reduce its effectiveness.

My paintings of human babies representing farmed/dead animals have caused a great deal of offence, especially when they’re displayed in public exhibitions, although no-one has actually found fault with the ideas, they just don’t like the visceral imagery. Love them or hate them, they are at least memorable!

Each painting is an act of controlled fury on my part, so I am always gratified to find that the work elicits strong responses. As it should.

Talk us through some of your favourite paintings.

‘The Ghost Camera’ – The one that started it all! A portrait of Jo-Anne McArthur surrounded by animals, some of whom were rescued from farms, and some of whom she had to leave – these are the ‘ghosts’ that haunt her.

‘The Ghost Camera’ – The one that started it all! A portrait of Jo-Anne McArthur surrounded by animals, some of whom were rescued from farms, and some of whom she had to leave – these are the ‘ghosts’ that haunt her.

MEAT

‘MEAT’ – a simple idea in which I just wanted to make the visceral/visual statement that ALL the meat we eat was once a baby.

Best of British

‘Best of British’ – Upon finding this harrowing photograph of a scene from a standard UK pig farm, I was so upset that I had to look away. So of course that meant that I had to paint it. I couldn’t let the pitiable sow in it be forgotten yet again. It hurts my heart to see this canvas and reminds me why I do what I do.

See How They Grow

‘See How They Grow’ – Male dairy calves are either shot and used for pet food, or raised in barbaric conditions for veal. Female calves are taken from their mothers, repeatedly impregnated, and milked to death over approximately 6 years before they are sent for slaughter. My ‘holstein babies’ emphasise the horror that lies behind the façade of the ‘happy, healthy’ milk industry.

One in a Million

‘One in a Million’ – Two million calves are born on UK farms every year. Each one an individual. The ear tags in the straw are a visual reference to these millions of discarded individuals, as well as being subtly and horribly reminiscent of the holocaust imagery of the second world war.

Journey’s End

‘Journey’s End’ – No matter where in the world a farm cow is born, their life’s journey always ends in the same way. I wanted to symbolically represent the inevitability of the bloody end of each and every life in a simple and mournfully poignant way. The title deliberately echoes the very famous world war one play of the same name.

Weanling

‘Weanling’ – The ‘weaning ring’ is placed on calves so that they can’t suckle, because the spikes hurt the mother. I was so shocked by the medieval-style cruelty of this commonly used item, that I wanted to make others feel the same way, assuming that if I didn’t know about this until recently, then most people wouldn’t either.

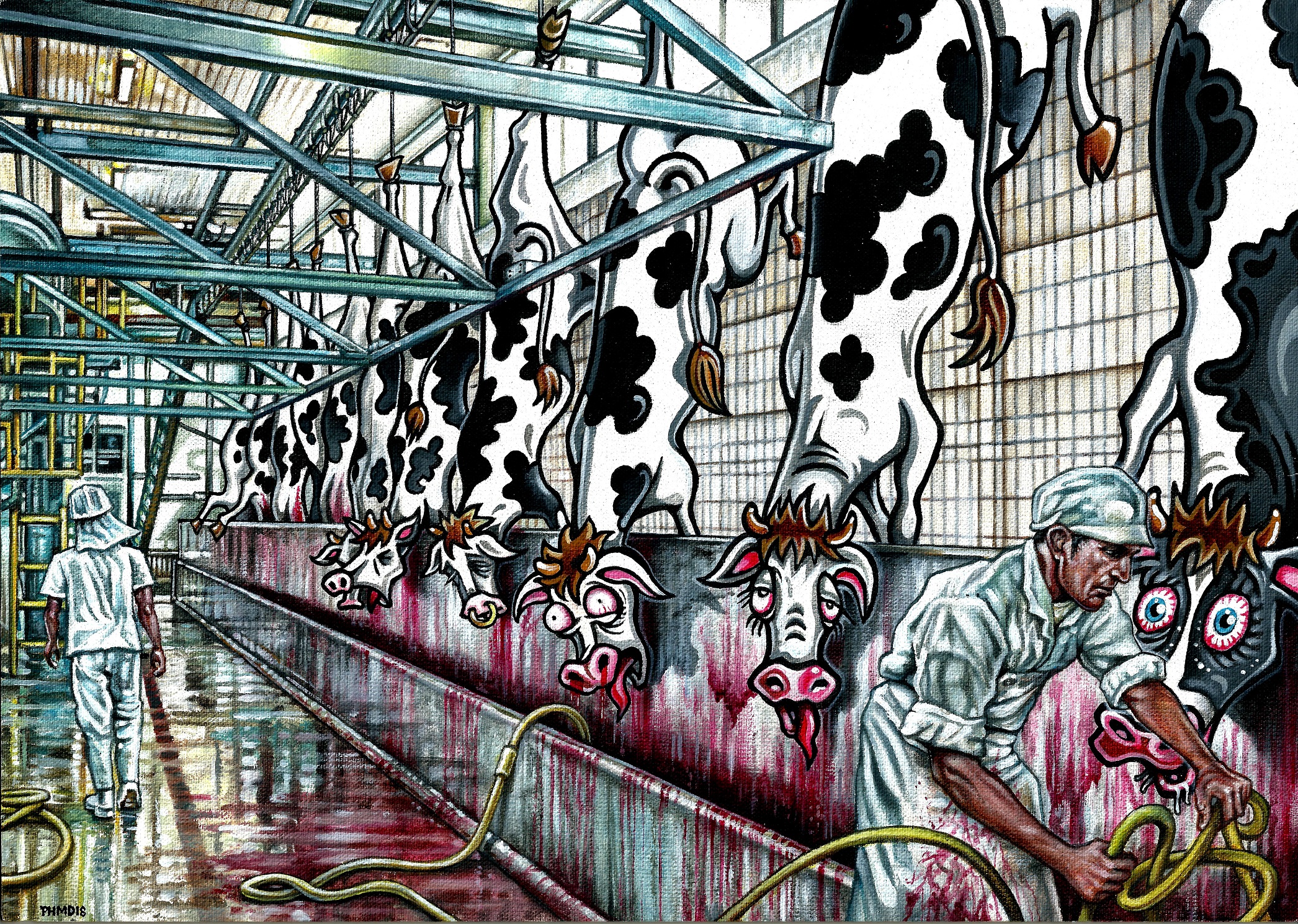

Marketing Myths #3

‘Marketing Myths #3’ – ‘Killing the cartoon’. Juxtaposing the infantile marketing imagery of the meat/dairy industry with the cold, hard reality of slaughter. It destroys the appealing myths that we would ALL like to believe. Showing it as cruelly as this offended the innocent child in me, and I found this one of the most upsetting images that I’ve ever painted.

How can people of faith take action in their personal lives and communities?

Lead by example. I have a great empathy with and respect for the kindness, mercy and compassion espoused by the stories about Jesus. To be a vegan in thought and deed seems to me to be perfectly in accordance with the principles of the Christian faith. Human health is entirely dependent on the substances you choose to build your body out of, and I believe that good spiritual health comes from a plant-based life. For me, promoting the protection of all animals whilst informing people of how easy it is to be vegan is the only morally and ethically correct way to live.

For more information and prints of Philip McCulloch-Downs’ work, visit his website www.philipdownsart.co.uk