On Easter morning, church bells ring and Christians greet one another with ancient words: Christ is risen.

We gather in light after darkness. We speak of life after death. We proclaim hope stronger than the grave.

Yet on the same morning, in the same country, slaughterhouses are operating as usual. Lambs are processed for seasonal demand. Chickens move along mechanised lines. Bodies become units. Units become products. Products become part of the Easter table. For most of us, these realities never meet. Resurrection belongs to church. Slaughter belongs somewhere else.

But what does resurrection mean in a world of slaughterhouses?

Since Easter is God’s decisive act in history, it must speak not only to humanity but to the whole fabric of embodied life. The empty tomb is not an escape from flesh. It is God’s verdict on flesh.

The resurrection of Jesus is not an escape from the body. The risen Christ is not a ghost. He bears wounds. He eats with his friends. He invites Thomas to touch his side. Easter is not God abandoning flesh but God vindicating it. The body that was tortured and executed is not discarded. It is raised.

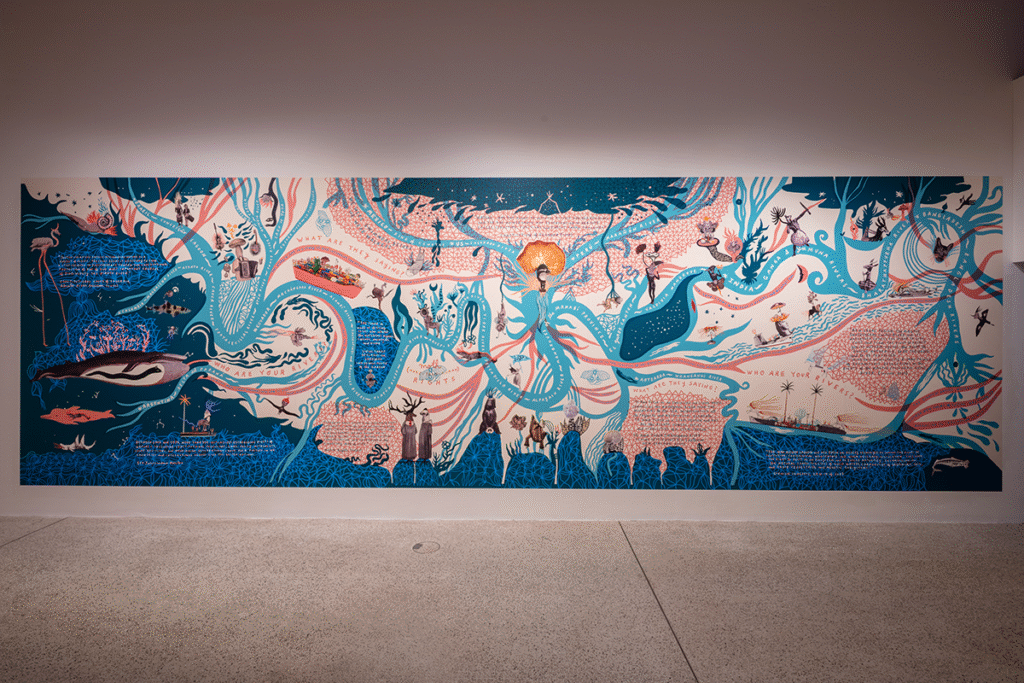

This matters. Christians sometimes speak as if salvation is about leaving earth behind. But the New Testament tells a different story. Resurrection is not the rejection of creation. It is its renewal. It is God’s refusal to let death have the final word over embodied life.

If that is true, then Easter is more than comfort for anxious humans. It is God’s great ‘Yes’ to creaturely existence itself.

Professor David Clough, theologian and author, reflecting on the work of Karl Barth, describes the work of Christ as affirming the Father’s ‘Yes’ to humanity. But he presses the question further: might this Yes extend beyond humanity?

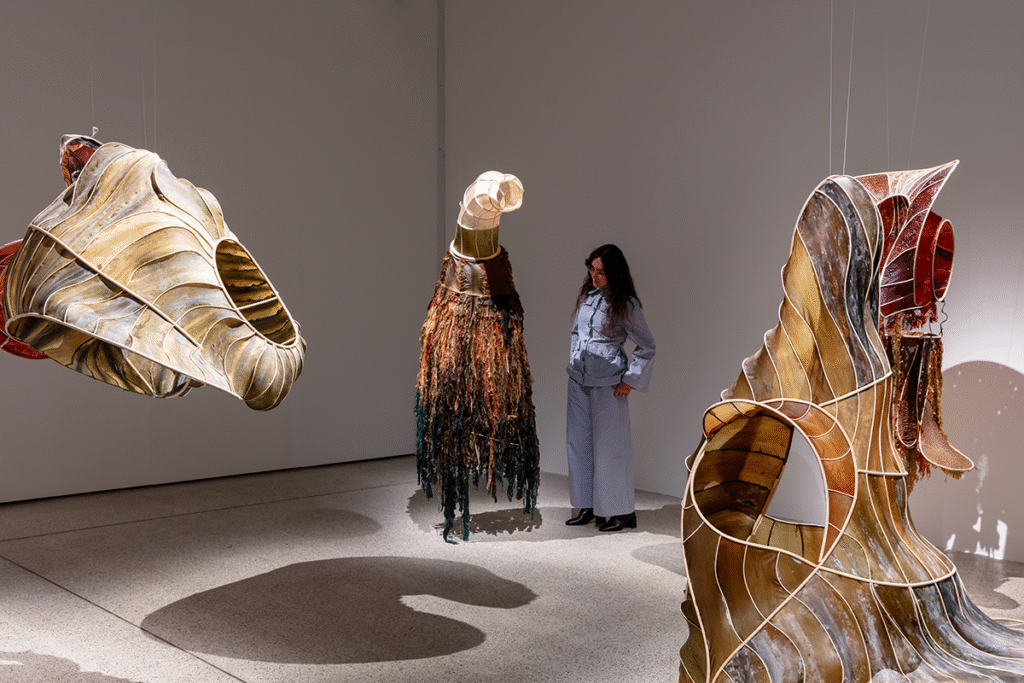

His answer is unequivocal. God’s grace is active towards all creatures. Barth even imagines human beings as arriving late to join ‘creation’s choir in heaven and earth, which has never ceased its praise’.

Christian faith begins not with human superiority but with creatureliness. We are beings made by God, dependent on grace, sharing existence with other beings who are also willed, sustained and loved by their creator. As Clough notes, theology cannot finally be anthropocentric. It must be theocentric. The God we worship made us together with other creatures and wills the flourishing of all.

Scripture itself gestures in this direction. The opening chapter of Genesis declares the goodness of the living world God has made. The closing chapters of Job remind us that the Creator delights in wild creatures beyond human control or usefulness. And in Romans 8, the apostle Paul writes that ‘the whole creation has been groaning’ as it waits for redemption.

If resurrection is God’s Yes to embodied life, it is not a Yes spoken over human bodies alone.

And this is where Easter becomes uncomfortable.

Because the world in which we proclaim resurrection is also a world organised around the systematic destruction of animal bodies. Not occasional necessity, but industrial design. Not survival, but efficiency.

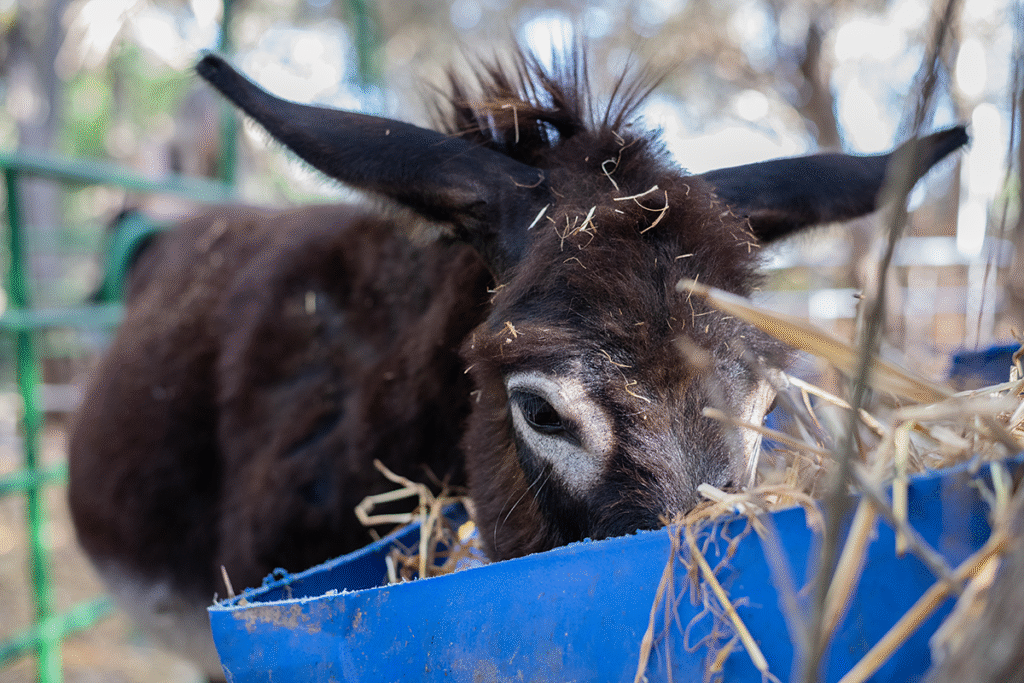

Billions of chickens are raised each year in featureless broiler sheds, bred to grow so quickly that their bodies often struggle to support their own weight. Pigs spend their lives in concrete warehouses. Dairy cows are separated from calves shortly after birth. Lambs become seasonal commodities.

This is not how most Christians imagine Easter. We think of spring, of flowers, of the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. Yet in our economy, lamb is also a product category. A demand curve. A promotional offer.

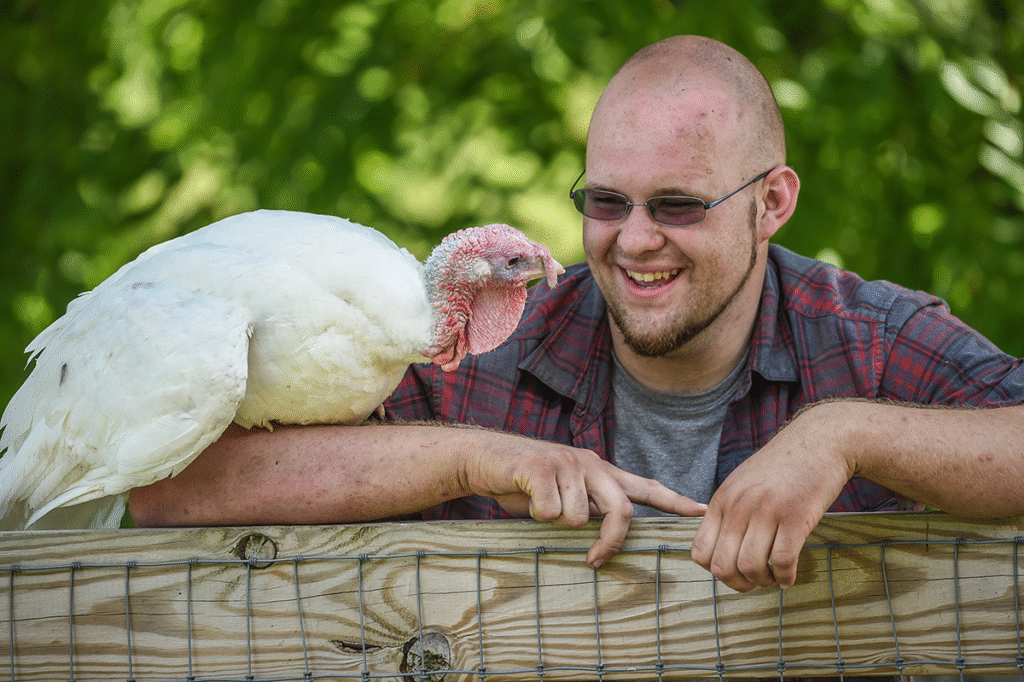

The question is not whether Jesus is present in suffering. The Christian story insists that God meets the world precisely in places of suffering and vulnerability. The harder question is whether we can proclaim God’s Yes to life while participating unquestioningly in systems of suffering that treat living beings as units of production.

If God wills the flourishing of creatures, what does it mean for Christians to consume animals raised in conditions with no regard for the ways they flourish?

Easter insists that bodies matter. That flesh is not disposable. That death does not define the limits of God’s concern. That claim cannot remain abstract.

Of course, none of this means that Easter should become a festival of guilt. The resurrection is not God’s accusation but God’s promise. It is the declaration that death and violence do not have the final word over the world God loves.

But promises invite response. Across the world today, tens of billions of animals are raised and killed for food each year. The systems that produce this meat are the result of modern technological and economic choices. And like all human systems, they can be questioned.

Christians have often led the way in challenging forms of cruelty that previous generations accepted as normal. From prison reform to the abolition of the slave trade, followers of Christ have sometimes been among the first to recognise that certain practices cannot sit comfortably alongside the gospel they proclaim.

The treatment of animals may be another such moment of awakening.

If Easter is God’s great Yes to life, then Christians might ask how their own lives can echo that Yes. Not perfectly. Not all at once. But meaningfully.

One simple place to begin is with the Easter table. Instead of celebrating resurrection with meat from animals raised in industrial systems, some Christians are choosing to mark the season with plant-based meals. It is a small act, but also a symbolic one. A way of aligning celebration with compassion. A way of allowing the hope of resurrection to shape not only what we believe but how we live.

After all, the risen Christ is not only the crucified one. He is also the Lamb of God, whose life reveals the self-giving love at the heart of God.

To follow that Lamb has always meant learning new ways of living in the world.

Perhaps this Easter, it might also mean discovering new ways of eating within it.