In recent years, questions about food, animals and Christian responsibility have moved from the margins to the centre of theological and ethical debate. As industrial farming intensifies, ecological crises deepen, and churches revisit what faithful discipleship looks like in a wounded world, long-standing assumptions about animal use are being re-examined. Christian Inspired Vegetarianism. Humans and Animals in the Divine Plan by Marilena Bogazzi enters this conversation with clarity and theological seriousness, asking whether care for animals belongs not merely to ethical reflection but to the spiritual heart of Christianity itself. Alma Massaro’s reflections on the book offer a careful guide through its scriptural, theological and historical arguments.

Latest News

Every November, millions of people around the world take part in World Vegan Month — a time to celebrate plant-based living and to reflect on our relationship with animals and the planet. For Christians, it offers more than a dietary challenge or lifestyle trend. It’s an opportunity to rediscover a deep current of compassion running through Scripture — a call to live in greater harmony with all God’s creatures.

Created for peace: animals in God’s story

From the very first chapter of Genesis, animals are not an afterthought but integral to creation’s goodness. God delights in the living world, blessing the animals and calling them “good” before humanity ever arrives on the scene. When humankind is created and given dominion over the earth, the same passage also sets a boundary — humans are to eat from the plants and trees (Genesis 1:29). Dominion, therefore, cannot mean domination. It is stewardship rooted in service, responsibility, and reverence.

After the Flood, God renews His covenant not only with Noah but with “every living creature of all flesh” (Genesis 9:12). The rainbow covenant is striking in its scope: it embraces sparrow and serpent, ox and whale, as well as humankind. God’s promises extend beyond the human family, revealing that animals are included in the moral and spiritual concern of the Creator.

The prophets envision the same truth in the language of hope. Isaiah imagines a time when “the wolf shall dwell with the lamb” and the earth shall be “full of the knowledge of the Lord” (Isaiah 11). This peaceable vision — echoed in Hosea and Revelation — portrays creation restored to its original harmony. In that kingdom, predation and fear are no more. To live toward such a vision is to align ourselves with God’s ultimate will for creation: reconciliation, not exploitation.

Christ and the creatures

Jesus’ ministry embodies that reconciling love. When challenged about healing on the Sabbath, He reminds His critics that anyone would rescue an animal fallen into a pit — for mercy outweighs rule-keeping (Matthew 12:11). His teaching assumes compassion for animals as natural and obvious. Elsewhere He points to God’s care for even the smallest of birds: “Not one of them is forgotten before God.”

The Lord’s frequent use of animal imagery — sheep, birds, vines, foxes — rests upon the real worth of those creatures. His description of Himself as the Good Shepherd presupposes that shepherds are meant to love and protect their flocks. A metaphor that comforted His listeners only makes sense if compassion for animals was itself a moral good. The shepherd who lays down his life for the sheep reflects divine love that extends through all living beings.

Throughout Christian history, this theme of compassion has never been lost. St Francis of Assisi spoke tenderly of “our brothers the birds” and called the sun, moon, and animals his kin. St Isaac the Syrian wrote that a merciful heart “burns with love for all creation: for people, for birds, for animals, even for demons.” More recently, C. S. Lewis condemned needless cruelty to animals as a betrayal of Christian conscience, reminding his readers that sentience itself demands moral regard.

In all these voices runs a common conviction: to follow Christ is to grow in mercy, and mercy cannot be confined to our own species.

Naming the wound

If the biblical and spiritual vision is one of harmony, the reality of modern animal agriculture reveals how far we have strayed. Each year tens of billions of land animals — and far more fish — are bred and slaughtered in industrial systems that prioritise profit over compassion.

Hens are confined to cages so small they cannot spread their wings. Pigs are kept in metal crates where they cannot turn around. Chickens are bred to grow so rapidly their legs buckle under their own weight. Many animals endure painful mutilations without anaesthetic and suffer immense stress and illness before slaughter.

Even those who rarely think about animal welfare instinctively recoil from such scenes. As philosopher Alastair Norcross once noted, if any neighbour were discovered keeping puppies in such conditions, the community would be horrified. Yet these same methods are routinely accepted when the victims are chickens or pigs.

Factory farming also harms people: it damages the environment, spreads zoonotic disease, and leaves workers traumatised by the conditions they witness. As Christians called to love both neighbour and creation, we cannot turn away. To inflict suffering on sentient creatures, when alternatives abound, contradicts the very heart of the Gospel.

Practising mercy this World Vegan Month

World Vegan Month offers a simple invitation: to align our daily habits more closely with our faith. Mercy can begin at the table.

Personally, you might try a vegan month as an act of discipleship — a spiritual discipline that joins compassion with gratitude. It needn’t be about perfection, but intention: choosing foods that honour life, seeking nourishment without harm, and discovering that plant-based meals can be joyful, abundant, and good for body and soul.

Within households and churches, November can become a season of creative hospitality:

- Host a plant-rich bring-and-share lunch or fellowship meal that celebrates God’s provision from the earth.

- Share vegan recipes through church newsletters or social media.

- Offer prayers of thanksgiving for creation and blessings for animals, echoing the covenant with “all flesh.”

- Encourage sermons or study groups exploring the biblical vision of peace between species.

Such practices can help Christians see that food choices are not trivial but deeply spiritual — expressions of love, justice and hope.

At an institutional level, churches and Christian organisations might review catering policies or move towards “default-veg” events where plant-based options are the norm. They can champion sustainable food systems, support local growers, and speak prophetically about compassion in agriculture. In a world where the poor are often most harmed by environmental damage, these steps also serve human justice.

A witness to the peaceable kingdom

Christianity has always proclaimed that creation is not ours to consume, but God’s to cherish. Each act of mercy, each choice to eat or live more gently, is a small sign of the kingdom Christ proclaimed — a world where every creature has its place and none are forgotten.

This November, as the wider world celebrates World Vegan Month, the Church has a chance to bear distinctive witness: to live out the covenant of peace with all living things. Our plates can become altars of thanksgiving; our meals, signs of God’s future. In turning away from unnecessary cruelty, we turn toward the One whose mercy is over all His works.

As the psalmist writes, “The Lord is good to all; His compassion is over all that He has made.” (Psalm 145:9)

May this compassion guide our hearts, our tables, and our witness — not only this month, but always.

St Francis of Assisi has long inspired Christians to see animals not as lesser beings, but as beloved fellow creatures—brothers and sisters under God. In this timely and thought-provoking article, Dr Daniela Rizzo, Associate Lecturer in Systematic Theology at Alphacrucis University College, Sydney, invites us to rediscover the radical implications of St Francis’ vision in the face of environmental crisis, mass extinction and theological neglect of non-human life.

In the beginning, God designed.

Not with blueprints or building codes, but with breath, beauty, and boundless compassion. Mountains were shaped, birds were feathered, whales were weighed in oceans of purpose. Every creature, from the lion to the ladybird, was part of this divine composition—made not for utility, but for joy.

Genesis tells us that God looked at all He had made and called it very good—not just the humans, but the whole interconnected tapestry of life. Trees, rivers, insects, elephants—all spoken into being by a Designer who delights in diversity and builds for relationship.

Yet somewhere along the way, we lost touch with that original vision. Our cities rose, our systems expanded, but too often they were built for humans alone. Roads cut through ancient migration paths. Buildings silenced birdsong. Farming practices inflicted suffering on the very creatures we were meant to care for.

Recently, London’s Design Museum concluded an exhibition titled More Than Human. Although the exhibition has now closed, its ideas remain deeply urgent. It invited visitors to reimagine the world not as a human-only domain, but as a shared home for all living beings. It asked a bold, almost sacred question: What if we designed the world not just for us, but for all creation?

A Design Language That Includes the Voiceless

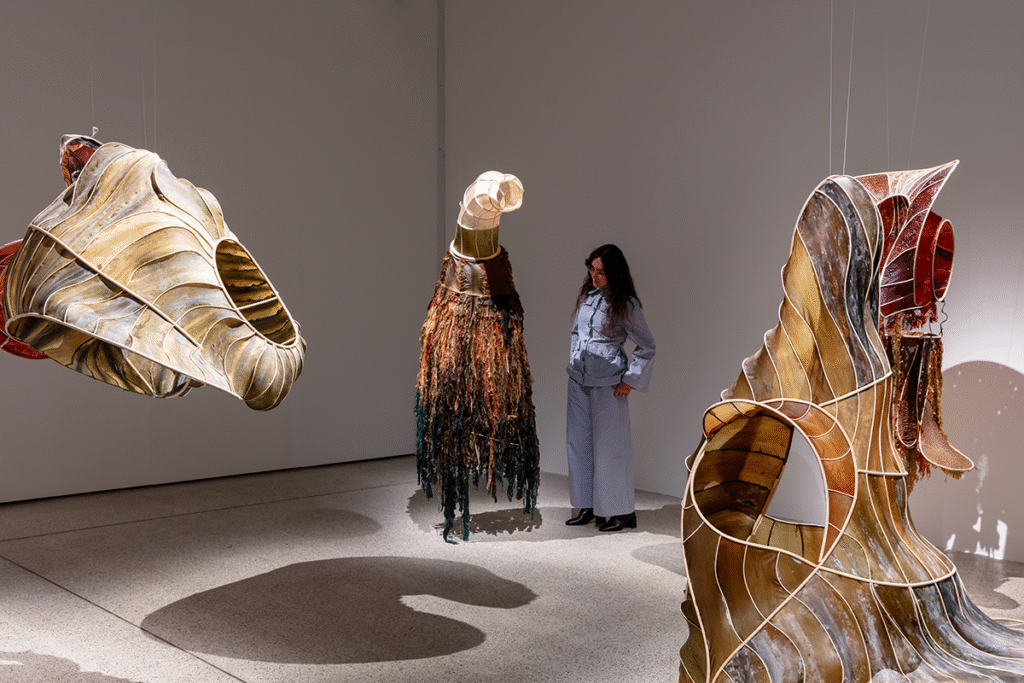

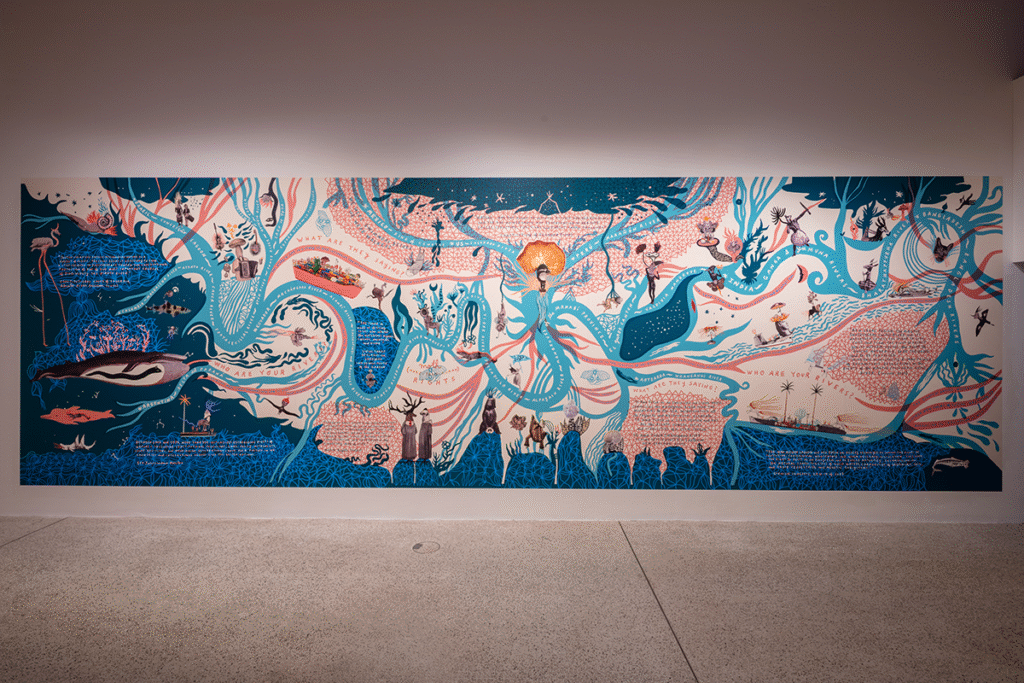

More Than Human showcased more than 140 works that looked beyond human needs to consider how animals, plants and ecosystems might flourish if they too were part of the design brief.

There was a tapestry recreating a meadow as seen by pollinators. Seaweed sculptures — “Kelp Council” — invited viewers to imagine interspecies collaboration. One pavilion-like structure was designed as a shared sanctuary for humans, birds and insects. Another installation used AI to interpret a river’s condition and translate it into human-readable signals, allowing the river to “speak”.

It offered a quietly revolutionary idea: design, when rooted in humility and imagination, can help repair what has been broken.

Even the Sandwiches Witness

During the exhibition’s run, the Design Museum made all its catering fully vegetarian and vegan. Not as a gimmick, but as a sincere expression of values.

“We wanted our food to reflect the heart of the exhibition,” the museum noted. “This is about our relationship with the environment and other species, and a commitment to reduce our carbon impact.”

For Christians, this resonates deeply. Food is never just food. Scripture shows meals as spiritual acts. Our dietary choices shape not just our bodies, but our witness. What we eat is part of the story we tell about who matters in God’s creation.

Peace with Creation: A Season and a Calling

This year’s Season of Creation, with its theme Peace with Creation, invited Christians to reflect on how we live, build and consume — and whether those actions bring harmony or harm.

More Than Human becomes a companion to this reflection. It doesn’t merely critique human impact on the environment. It dares to imagine an alternative. It reclaims design as a sacred act of care — echoing the Genesis vocation to “serve and protect” the garden (Genesis 2.15).

Isaiah envisioned a world where no one hurts or destroys on God’s holy mountain. Paul writes of creation groaning for liberation. Jesus assures us that not even a sparrow falls outside the Father’s care. The exhibition, though not religious, carried these resonances — a signpost, in N. T. Wright’s words, pointing toward the Kingdom.

The Gospel According to Design

We do not need to be architects to respond. All of us are designing something — habits, homes, schedules, lives. Every choice is a blueprint for the kind of world we want to inhabit.

Choosing plant-based meals. Supporting ethical fashion. Creating pollinator space in our gardens. Campaigning for laws that protect ecosystems. Teaching our children to notice and name the birds.

All of these are acts of co-creation.

God, the First Designer, invites us not to stand above creation but within it — to design with empathy and build with reverence. To eat with gratitude and restraint. To act for the voiceless and safeguard the vulnerable.

This Season of Creation, may we design lives that reflect the love of the One who crafted every wing, paw and petal. May our choices preach peace. May we help build a world where once again God might look at all He has made — and call it very good.

Will the animals we know and love be in heaven?

In his latest book A Heaven for Animals: A Catholic Case and Why It Matters, Jesuit theologian and ethicist Christopher Steck offers a thoughtful, hope-filled answer. Drawing on Scripture, Catholic tradition, and the writings of Popes John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis, he makes the case that God’s redemptive work includes not only humanity but also the nonhuman creatures with whom we share this life.

But for Fr Steck, this hope is not merely a distant dream—it has consequences for how Christians live today. If animals are part of the new creation, then our relationships with them matter now, and our choices should reflect the kingdom values of harmony, compassion, and justice.

In the excerpts below, Fr Steck first explores out the theological foundation for including animals in God’s eternal covenant, and then challenges us to consider the ethical implications for our treatment of animals in the present.

Excerpt from Chapter 4, Contemporary Magisterial Views of Animals and Their Salvation, p.82

Denying salvation to the sentient animals that have lived in this present age goes against the logic of God’s redemptive work. God loved individual creatures into existence. God is the God of relationships and wants to enter into a covenant with all creatures. It would be odd for God, who loved the present world into existence, to discard the old and simply create a new version of it. The animals that exist here and now are part of our lives, part of human history; sometimes they have shaped our lives in profound ways. Our relationships with them have been life-giving to us and, we hope, to the animals themselves. Preserving one side of creaturely relationships (the human part) while abandoning the other (the nonhuman part) seems contrary to the covenantal hopes that God achieved in Christ.

I read Pope Francis as advocating an inclusive view of the resurrection in his theology of creation. He repeatedly reminds us that God cares for each creature—not just for creation in general but for the concrete, individual creatures within it.

Excerpt from Chapter 8, Animal Ethics: Applied, p.152

Typical practices in meat production reflect neither the way God values creation nor the Christian task of bringing God’s creatures into the liberation of the kingdom. Not all Christians are required to embody kingdom values of harmony and friendship with animals by abstaining from meat, but it does seem important to avoid when possible practices that are so pointedly antithetical to those values and witness to the alternatives. The duty of the entire Christian community is to act before others in ways that edify and build up, even when and perhaps especially when those practices upend and destabilize socially engrained expectations about how we are to relate to nonhuman creatures.

Learn More

Christopher Steck SJ is a Jesuit priest and the Healey Family Distinguished Professor at Georgetown University where he teaches courses in Christian ethics and moral theology. His research focuses on the intersection of theology, ethics, and the natural world, with a special interest in Catholic teaching on the moral status of animals.

Fr Steck is the author of A Heaven for Animals: A Catholic Case and Why It Matters and has published on ecological ethics and the theological foundations for creation care.

Excepts published with permission from Georgetown University Press.

Why do so few Christians talk about animals—and what might happen if we did? In this honest and thought-provoking interview, philosopher and theologian Simon Kittle reflects on his journey towards a deeper compassion for all creatures. Drawing on insights from his new book God and Non-Human Animals, Simon explores the blind spots in Christian thinking, the emotional cost of change, and why the Church still finds it hard to take animal suffering seriously. Challenging but full of grace, his words invite us to rethink what faithfulness really looks like in a world shared with fellow creatures.

In glossy adverts and sizzling billboards, meat is rarely just food. It is sex, power, and desire on a plate.

Fast-food chains, steakhouse commercials, and celebrity chefs sell meat through the language of lust: dripping juices, flesh torn apart, women seductively holding burgers.

As Carol J. Adams observes in her seminal work The Sexual Politics of Meat, meat advertising often sexualises both the flesh and the act of consumption itself, portraying meat-eating as an assertion of dominance, virility, and entitlement. This is no accident. Adams argues that meat is marketed to stimulate lust—not only for the food itself, but for what it represents: power, conquest, and status. In this light, our culture’s insatiable appetite for meat is not simply about satisfying hunger—it is about craving, addiction, and fantasies of dominance over others, both animal and human.

Modern fast food culture further fuels this dynamic by engineering products to reach the so-called “bliss point”—a calculated balance of animal fats, salt, and sugars that maximises desire and suppresses satiety. The result is not just nourishment, but a deliberately addictive form of consumption.

This modern phenomenon might seem far removed from the ancient world of the Bible. Yet when we turn to Deuteronomy 12, we find something remarkable: the Bible itself uses the language of lust, craving, and disordered desire when speaking of meat-eating. Far from celebrating the consumption of animal flesh, the Hebrew Scriptures frame it as a reluctant concession to human lust—a dangerous craving that must be carefully regulated, not enthusiastically indulged.

This ancient insight speaks with unsettling relevance to our flesh-obsessed, consumption-addicted culture today.

The Edenic Diet: Before Lust, There Was Peace

To understand Deuteronomy 12, we must first place it within the broader sweep of biblical narrative.

The Bible begins not with slaughter but with peace. The opening chapters of Genesis depict Eden as a plant-based paradise. God’s provision for both humans and animals is clear: “I give you every seed-bearing plant… They will be yours for food” (Genesis 1:29–30). There is no death, no bloodshed, no butchery. As Martin Luther once wrote, in this Edenic world, the killing of animals would have been considered an “abomination.”

This original harmony is shattered by human rebellion in Genesis 3. As sin enters the world, violence and death become part of the human condition. Only after the Flood, when arable agriculture had been destroyed, does God extend permission for humans to eat animals (Genesis 9).

Even so, the tone of the permission is sombre and laced with warnings: “The fear and dread of you shall rest on every animal… for your own lifeblood I will surely require a reckoning” (Genesis 9:2, 5). Notably, this permission lacks the divine affirmation that it was “good,” let alone “very good,” which accompanied the plant-based diet of Genesis 1.

Deuteronomy 12: The Meat of Lust

It is in this context that Deuteronomy 12 must be read.

At first glance, the passage appears to give Israelites wide freedom to slaughter and eat meat outside the sacrificial system, avoiding its strict welfare regulations. They are told: “When the Lord your God enlarges your territory… you may eat meat whenever you desire” (Deuteronomy 12:20). On the surface, this seems generous—even celebratory.

Yet beneath the English translation lies a darker current.

The Hebrew text repeatedly uses forms of the verb ’avah (אָוָה), connoting lust, craving, and unruly desire. This is no neutral term for appetite. It is the same root used in Genesis 3:6 to describe Eve’s desire for the forbidden fruit, in Numbers 11 when the Israelites lusted after meat in the wilderness, and in Psalm 78:30 where their craving provoked divine judgment.

Indeed, Numbers 11 offers the most sobering parallel. When the Israelites cried out for meat, God gave them quail in abundance—but followed it with a deadly plague. The place was named Kibroth Hattaavah—“the graves of lust”—a stark reminder of where disordered desires can lead.

Many Jewish commentators recognise this theme running through Deuteronomy 12. Richard H. Schwartz, quoting Torah scholar Nehama Leibowitz, describes the passage as a “barely tolerated dispensation” to slaughter animals if we cannot resist temptation. Some Jewish communities still refer to such meat as b’sar ta’avah—“meat of lust”—a telling phrase that casts such consumption in a morally ambiguous light.

Far from celebrating meat-eating, Deuteronomy 12 offers a regulated outlet for a dangerous human craving—meant to prevent even worse consequences, such as idolatrous sacrifices or violent rebellion.

Biblical Restrictions: A Curb on Human Appetite

The broader Torah reinforces this sobering picture. The sacrificial system itself was highly restrictive. Slaughter could only take place at the central cultic site, overseen by priests. The blood—representing life—was never to be consumed but poured out in recognition of life’s sanctity. Fat, the most flavourful part of the animal, was forbidden to the people and reserved for God alone.

Even the method of cooking was regulated. Boiling, not roasting, was prescribed—producing a gristly, unappealing stew. Roasted meat, which melts fats and produces sugars through caramelisation (creating the bliss point exploited by modern fast-food chains), was viewed with suspicion. The sons of Eli were condemned for demanding roasted meat—an act that revealed not only greed, but sacrilege (1 Samuel 2:12–17).

These laws served not only to ensure ritual purity and minimise cruelty, but also to curb human lust for animal flesh. It may have been necessary to slaughter animals to maintain a balanced herd, but eating their flesh was carefully regulated—to reduce harm to animals and to humans alike.

A Pattern of Concession, Not Celebration

Throughout the Old Testament, we see a pattern emerge: certain actions—kingship, slavery, divorce, war brides, and indeed meat-eating—are permitted by God not because they are good, but because of human hardness of heart.

Jesus himself identifies this pattern when he tells the Pharisees that Moses permitted divorce “because your hearts were hard”—but it was not so from the beginning (Matthew 19:8). The same could be said of meat-eating.

Even within Deuteronomy, the permission to eat meat is framed by language of lust, desire, and rebellion. It is a tolerated practice within a fallen world—carefully controlled to limit the damage it causes to animals, to people, and to the covenant community.

From Concession to Compassion: A Prophetic Trajectory

The trajectory of Scripture moves beyond these reluctant concessions toward a vision of peace, harmony, and reconciliation with all creatures.

The prophets envision a world where swords are beaten into ploughshares—and, significantly, not into slaughter knives. The wolf lies down with the lamb (Isaiah 11:6). The New Testament speaks of creation groaning for liberation (Romans 8:19–21), and Christ’s work is described as reconciling “all things” in heaven and on earth (Colossians 1:20).

In this eschatological light, the Bible’s reluctant permissions are not the last word. They point instead to God’s accommodation to human weakness—while gently urging us toward mercy, compassion, and peace.

A Forgotten Theology for a Hungry World

In our age of industrial animal agriculture, climate crisis, and unprecedented violence against animals, the ancient warnings about meat of lust feel tragically relevant. Unlike the subsistence farming of the Bible, slaughter is no longer necessary in wealthy nations.

Our culture’s voracious appetite for meat is rarely framed as lust—yet the parallels to biblical warnings are hard to miss: mass suffering, environmental devastation, and the commodification of life itself.

Far from outdated, this neglected thread of Scripture may offer the Church a prophetic voice in our food-sick, consumption-addicted world. It may call us not to judgment or legalism, but to humility, restraint, and a rediscovery of animals—not as meat, but as fellow creatures of God’s love.

Perhaps it’s time the Church dared to question the products on supermarket shelves and ask: Is this ‘meat of lust’? And if so, is this really what God desires for his people?

About the Author

This article was written by a member of the Sarx staff team, with grateful acknowledgment to Dr Philip J. Sampson FOCAE for his scholarly insight.

Dr Sampson is a writer and lecturer on animals and animal ethics. His publications include Animal Ethics and the Nonconformist Conscience (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018); “The Ethics of Eating in ‘Evangelical’ Discourse: 1600–1876,” in Ethical Vegetarianism and Veganism, eds. Andrew Linzey and Clair Linzey (Routledge, 2018) and “Evangelical Christianity: Lord of Creation or Animal among Animals?” in The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Animal Ethics (Routledge, 2018).

Dr Daniela Rizzo, Associate Lecturer in Systematic Theology at Alphacrucis University College, Sydney, explores the presence of the Spirit within the animal world in this beautifully reflective piece. Drawing on her research in animal theology and pneumatology, Dr Rizzo invites us to reimagine the creatures around us as vital participants in God’s living world, animated and sustained by the breath of God.

Art has long held a prophetic voice in society—a voice that does not merely echo the status quo, but challenges it. Through brushstrokes, sculpture, song, or spoken word, art has the potential to pierce the veil of everyday life and reveal the deeper truths often obscured by power, tradition, or economic interest.

One artist doing precisely that is Philip McCulloch-Downs, whose work Marketing Myths strips away the cheery façade of the meat industry to expose the haunting reality of animal suffering. By highlighting how marketing campaigns distort our understanding of the animals we consume, McCulloch-Downs calls us to see the world—and our relationship with animals—with unclouded eyes and compassionate hearts.

What does it mean for Christians to pray, “Give us this day our daily bread”? In this thought-provoking reflection, Professor David Clough explores the profound ethical implications of this familiar petition. Drawing on scripture, theology, and contemporary food justice concerns, he challenges us to consider how our food choices impact our human and non-human neighbours.