Trevor Bechtel, Lecturer at the University of Michigan, considers how some individual animals became famous, not only for what they did, but also for the deep and profound relationships that they shared with their human companions.

One of my favorite stories of the last several months is the story of Gunner, a small Cavalier King Charles Spaniel who lives with Richard Wilbanks in Florida. Gunner is internet famous because of this incredible video which shows Richard wrestling the alligator who sought to snack on Gunner.[1] Gunner gives us a great opportunity to explore the beginnings of a theology of animal celebrity even though Gunner is famous simply for being caught on video. In the video Gunner doesn’t do anything to merit his fame; the alligator and the human do all the work. But Gunner embodies the thesis of this chapter in a profound way. I’ve heard this thesis narrated many times in different ways by different people–most powerfully by a woman who I used to work with who lost her father when he jumped in a frozen lake to save his dog losing his own life in the process. The thesis is, at least in the form it exists between dogs and humans, one of the oldest truths about who we are as humans. It is that we care about what each other cares about. Humans and dogs have been doing this for at least 14,000 years and likely at least three times that long.[2] This care, and the fact that when talking about dogs and humans we are definitely talking about a “we” grounds the possibility that animals have much to teach us about what it means to be human, and that this might be paradigmatically so when we approach the animal celebrity.

A King Charles Spaniel puppy similar to Gunner

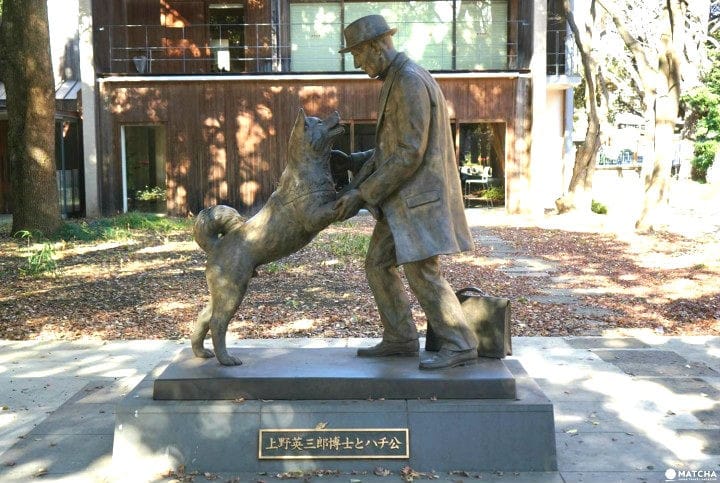

My favorite canine celebrity is Hachiko who began living with a professor at the University of Tokyo in 1924. Every day Hachikō would go down to the Shibuya Train Station and wait for the professor. The professor died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1925 and stopped going to the train station. But Hachikō kept going, although the humans at the train station could be rude to him. In 1932, interested in the Hachikō’s breed (Akita, a dog very closely related to wolves) one of the professor’s former students followed Hachikō back to the professor’s gardener’s home. The gardener explained the story of Hachikō to the student who eventually wrote a story which was published in a Tokyo newspaper. Hachikō became famous in Japan for his loyalty. Hachikō died in 1935. He was stuffed and put in the National Science Museum in Japan. A statue of him was erected. Hachikō became the exemplar of loyalty in Japan. Children, and others, were urged to follow his example. At the Shibuya train station the station gate next to the statue is called the Hachikō gate. There two more statues in Odate, Hachikō’s hometown, and one at the Woonsocket Depot Square in Woonsocket, Rhode Island.

There are stories of human loyalty which may meet Hachikō’s example, but none exceed it. The professor and Hachikō connected for a little bit longer than a year, but then Hachikō remained loyal for seven years before even receiving any acclaim. Hachikō is one of the most important creatures you can talk about when you talk about loyalty. He is obviously very famous. Hachikō, the Wolf of Gubbio, and Gunner have a lot in common, at least genetically, but also in that they are defined in our imagination because of their relationships.

A bronze statue of Hachiko along with his beloved professor (Shibuya, Tokyo)

There is video and and photographic evidence of these two dogs, but for the purposes of thinking about their celebrity, it hardly matters. Indeed, according to John Blewitt, “In looking at the use, depiction and presentation of non-human others in culture, politics, sport, art, science and so on, we engage in a relational exercise that is as much about us as them. Animal celebrity is a human construct and tells us something about the human socially constructed natural world in the bargain.”[3]

What are some of things we learn? Well we learn about the nature of celebrity and charisma when we realize that these qualities are not limited to humans. Blewitt’s notes that charisma originally denotes a virtuous “gift of grace” that sets an individual apart from the everyday. The charismatic authority of the celebrity and the saint teach us what it means to be human as we imagine how some individuals transcend the everyday or negotiate the sacred and profane. Blewitt continues, “Thus celebrity and charisma, human and non-human, are frequently entwined. If not exactly divine, then celebrity and charisma are arguably twin aspects of symbolic power emerging from something that is a mongrel – a cross between a chimera and a simulacrum. They are both beyond the everyday and, through their cultural pervasiveness, soundly of the everyday”[4]

We also learn about the importance of individual animals. We often think of animals in terms of their species; Akita or Cavalier King Charles Spaniel but even Gunner is decisively an individual. We, as individual humans can’t have relationships with a species. Instead we relate to individual animals, and animal celebrities remind us of the importance of the individual animals we relate to. In fact this relationship to an individual might explain why so many animal celebrities have ended up stuffed. Hachikō was stuffed, Dolly the sheep was stuffed, even Jumbo the elephant famous on two continents at the end of the 19th century was stuffed, perhaps so people could continue to relate to the individual that they had known. We can still visit Hachikō at the National Science Museum in Japan.

While Hachikō’s celebrity is focused on moral authority, Gunner’s celebrity illuminates the entire web of relations that we find ourselves caught up in. We know of Gunner’s close relationship to his humans, Louise and Richard. But Gunner is also connected to creatures that live in the more wild areas close to his home. In an interview after Gunner and he had healed, Richard Wilbanks reports, “The alligator is still in the pond. It’s just fine. Gunner is fine, I’m fine and so am I,”[5] The camera that shot the footage belongs to the fStop foundation who use it and hundreds like it to capture images of the deer and bobcats and myriad other creatures which inhabit the ecologies of Northern Florida. One of their goals is to educate the surrounding public of the presence of these animals. Gunner has helped them immensely in this task. His celebrity becomes the charismatic authority of ecological protection and safety. And he has now been recognized for that having been deputized at the end of last year. [6]

I want to push this point just a bit further. The Belgian philosopher Vinciane Despret suggests that when we can engage famous animals and those who relate to these animals as, “seeing themselves just as we would see ourselves if we were in their position” we open ourselves to “a particular form of perspectivism (which is) much better situated to define a certain dimension of self-consciousness, no longer as a cognitive process but as an interrelational process.”[7]

The dogs I have surveyed in this paper are famous for the things that they did, but they are also famous because of their relationships to humans. With certain adjustments their celebrity could be compared to a kind of sainthood. Internet virality might replace the miracle, although many animal celebrities are quite miraculous. But more seriously, although many will be anxious about ascribing virtue, cardinal or theological, to animals the stories in this essay reveal that in their relationality, animals show us the path to virtue, if not virtue itself. And they do this meaningfully especially when considered inside the rubric of celebrity.

[1] “Sharing the Landscape – Rick, Gunner, and the gator.” fStop Foundation, November 25, 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JEWG1R7lZOA

[2] Janssens et al, “A new look at an old dog: Bonn-Oberkassel reconsidered”,

Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 92, 2018, Pages 126-138.

[3] John Blewitt, “What’s new pussycat? A genealogy of animal celebrity”, Celebrity Studies, 4:3, 2013, 325-338. p. 326.

[4] Ibid, p. 331.

[5] Carolina Cardona, “Puppy pried from gator’s mouth by his human doing just fine”, November 24, 2020, https://www.clickorlando.com/news/local/2020/11/24/puppy-pried-from-gators-mouth-by-his-human-doing-just-fine/

[6] Joe Mario Pedersen “Florida man pulls dog out gator jaws; dog made sheriff’s deputy”, Orlando Sentinel, December 10, 2020, https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/florida/os-ne-dog-survives-gator-attack-deputized-safety-security-officer-20201210-ghmhgkx2vfdvthoe3maoxh3gju-story.html

[7] Vinciane Despret, What Would Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016, p.32.

Trevor is a Lecturer at the University of Michigan where provides leadership and oversight to several research projects, including the Prosecutor Transparency Project, and he engages students who seek to connect to Poverty Solutions by facilitating a variety of programs, events, and research opportunities.

He holds a doctorate in constructive theology from Loyola University Chicago and has published “The Gift of Ethics” (2014) and “Encountering Earth: Thinking Theologically With a More-Than-Human World” (2018) with Cascade Press.