Christmas is a season of abundance. Tables groan under food. Kitchens fill with the familiar smells of roasting, herbs and spice. Families gather, traditions are honoured, and we reassure ourselves that this is what celebration looks like.

And yet Christmas tells another story.

It is the story of a God who enters the world quietly and without excess. A child born among animals, not above them (Luke 2:7). A saviour whose first bed is a feeding trough, whose arrival is announced not to the powerful but to shepherds keeping watch through the night. Christmas does not begin with triumph, but with vulnerability.

Which raises an unsettling question, one we rarely ask amid the festivities:

What would Jesus eat for Christmas?

Not as a matter of dietary preference, nor as a test of moral purity, but as a question of faithfulness. What kind of table would reflect the kingdom his birth announces?

Christmas words and Christmas habits

When Christians speak about Christmas, certain words come easily. Good news. Great joy (Luke 2:10). Peace on earth (Luke 2:14). Love. Hope. We sing of angels and light and reconciliation. We proclaim Christ as the Prince of Peace, the one who comes to establish a kingdom of justice and righteousness (Isaiah 9:6–7).

It is striking, then, how seamlessly another word has joined this vocabulary: meat. In the UK, turkey has become so closely associated with Christmas that it feels almost inevitable, as though it were woven into the fabric of the feast itself.

Yet this association is not ancient, nor biblical. Turkey was unknown in Britain until the sixteenth century and only became widespread centuries later. What feels timeless is, in fact, remarkably recent. And more recent still are the systems that now produce Christmas meat at scale.

This matters, because Christmas is not only a celebration of what has been. It is also a sign of what is coming. To ask what belongs at the Christmas table is to ask what kind of world we are welcoming into being.

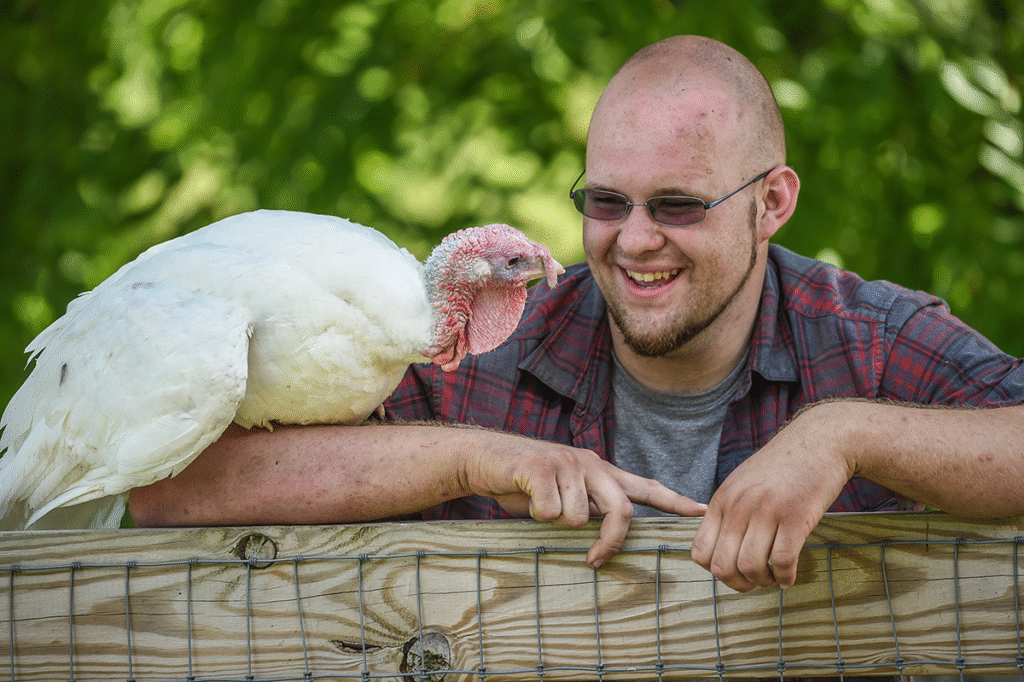

The animals of the manger and the animals of the market

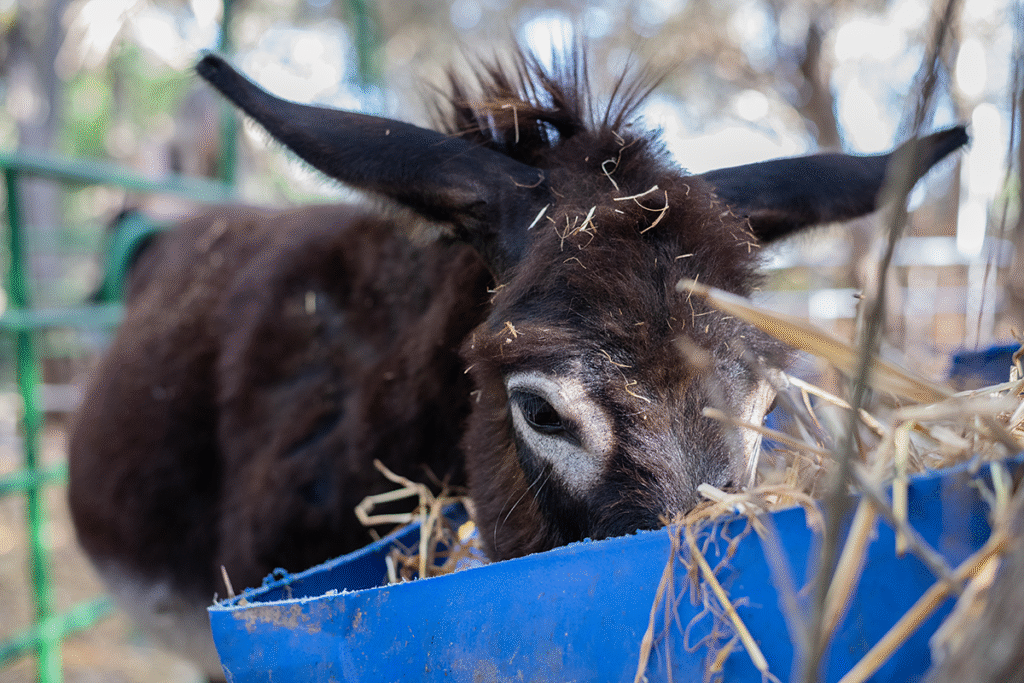

The Nativity story is crowded with animals. Ox and ass, sheep and lamb, creatures who appear not as decoration but as companions to God’s arrival in flesh. The incarnation takes place in their midst. God chooses to be born into the shared life of creatures.

This should not surprise us. Scripture consistently affirms that animals belong to God and matter to God. ‘The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it’ (Psalm 24:1). God declares animals good (Genesis 1:24–25), delights in them (Psalm 104:31), includes them in covenant (Genesis 9:8–10), and promises their restoration alongside humanity (Isaiah 11:6–9; Colossians 1:20).

And yet, in our celebrations, animals appear in a very different form. Not as fellow creatures, but as products. Not as lives, but as portions. Their suffering is kept at a distance, hidden behind packaging, advertising, and tradition.

The dissonance is easy to miss because it is normalised. Most of us have inherited a way of thinking in which some animals are to be cherished, others consumed, and the lines between them feel natural rather than cultural. Scripture repeatedly challenges this complacency. ‘The righteous know the needs of their animals,’ Proverbs tells us, ‘but the mercy of the wicked is cruel’ (Proverbs 12:10).

Christmas intensifies this challenge rather than softening it. In Jesus, God does not hover above creation but enters it. The Word becomes flesh (John 1:14), not as an abstraction, but as a vulnerable body dependent on the care of others, human and non-human alike.

Concession, not celebration

Some will object that Jesus himself ate meat. The Gospels place him within the food practices of his time, and it would be disingenuous to deny that. But this observation is often used too quickly, as though it settles the question rather than opens it.

Even if Jesus shared in the food practices of his time — eating fish, participating in festival meals — that world bears little resemblance to an age of industrial farming, hidden slaughter, and global supply chains that turn lives into commodities.

The Bible itself treats the eating of animals with caution. In the opening vision of creation, humans and animals alike are given plants for food (Genesis 1:29–30). Violence is absent from God’s declaration that creation is ‘very good’ (Genesis 1:31). Permission to eat animals appears later, after the flood, framed not as an ideal but as a concession to a fractured world (Genesis 9:3–5), accompanied by fear, dread, and a warning that life is not to be taken lightly.

This tension runs throughout scripture. Meat is permitted, but never celebrated as God’s best intention. Care for animals is repeatedly mandated, even when it conflicts with efficiency or profit (Deuteronomy 25:4; Exodus 23:12). Limits are placed on human appetite. Restraint is treated as a moral good.

Jesus himself points to this pattern when he speaks of certain practices being allowed ‘because of your hardness of heart’, but not reflecting God’s original intention (Matthew 19:8). Christmas belongs firmly within this story. It does not erase human brokenness, but neither does it bless it. The incarnation is God’s way of entering a compromised world in order to heal it, not endorse all its habits.

For Christians, this opens the possibility of seeing plant-based eating not as a rule to be enforced, but as a sign — however partial — of the peace we long for and await.

Eating in expectation of the kingdom

Christian faith is shaped not only by memory, but by expectation. The angels’ proclamation of peace is not wishful thinking. It is a promise. A declaration that history is bending towards reconciliation.

The prophets imagined this future as a peaceable kingdom, a world in which violence no longer governs relationships between creatures (Isaiah 11:6–9). The New Testament insists that, in Christ, this future has already begun. Creation itself, Paul writes, longs for liberation and renewal (Romans 8:19–22).

Christians are called to live now in the light of what is coming, to practise — imperfectly — the life of the kingdom. ‘Put off the old self,’ Paul urges, ‘and clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience’ (Colossians 3:9–12).

Food is part of this practice. Eating is never merely biological. It is cultural, social, and deeply symbolic. What we choose to eat, and how it is produced, reflects what we value and whose lives we consider expendable.

Christmas feasts are not just meals. They are rehearsals of what we believe celebration should look like. They tell a story about abundance, belonging, and whose lives count.

Peace on earth, at the table

At Christmas, peace is everywhere in our language and music. We sing of it, pray for it, exchange it in greetings. Yet peace, in the biblical imagination, is never abstract. It is practised, embodied, and tested in ordinary decisions. ‘Seek peace and pursue it’ (Psalm 34:14).

The industrial systems that now dominate animal agriculture sit uneasily with this vision. In the UK alone, millions of animals eaten at Christmas are reared in intensive indoor systems designed for efficiency rather than care. Suffering is not an accident of these systems, but a condition of their success.

Jesus consistently challenges forms of power that prioritise gain over mercy. He reminds his followers that God desires compassion, not sacrifice (Matthew 9:13), and warns against piety that obscures harm. It is difficult to imagine that the relentless suffering built into modern food systems would sit comfortably with the one who identified himself with ‘the least of these’ (Matthew 25:40).

Christmas invites us to look again. Not to condemn ourselves or others, but to notice the gap between what we celebrate and what we sustain.

A different kind of abundance

One of the quiet fears beneath resistance to change is the fear of loss. That a Christmas without meat would be diminished, joyless, less generous. Yet this assumption says more about habit than about reality.

Scripture repeatedly insists that God’s abundance does not depend on exploitation. ‘The Lord is good to all, and his compassion is over all that he has made’ (Psalm 145:9). Across cultures, plant-based food has long been associated with feasting, hospitality, and delight. What is often framed as sacrifice may, in practice, be a recovery of abundance from excess.

Seen this way, choosing compassion at Christmas is not about asceticism or self-denial. It is about alignment. About allowing the story we tell in word and song to be echoed, however imperfectly, in how we live.

For some, faithfulness this Christmas may mean trying a fully plant-based meal. For others, it may begin with smaller acts — centring vegetables rather than meat, choosing higher-welfare alternatives, or simply allowing discomfort to interrupt habit. Christmas rarely asks for perfection, but it often invites first steps.

What would faithfulness look like?

The question ‘What would Jesus eat for Christmas?’ is not meant to produce a single, uniform answer. It is meant to unsettle us just enough to create space for reflection.

Would our tables look the same if we took seriously the vulnerability at the heart of the Nativity? If we allowed the angels’ song of peace to reach beyond sentiment and into practice? If we remembered that the kingdom Christ inaugurates includes not only humanity, but ‘all things, whether on earth or in heaven’ (Colossians 1:20)?

Perhaps the most faithful Christmas table is not the one that preserves every tradition, but the one that dares to ask whether those traditions still serve the good news we celebrate.

If Christmas proclaims peace on earth, then it is worth asking — quietly, honestly — whether a feast of peace can depend on hidden violence.